Bussiness

40 years ago today, Ford closure was the lowest point in Cork’s industrial story

In many ways, the tree-lined street provides a walk down Cork’s industrial memory lane.

Today, you pass by the wonderful Marina Market with its teeming stalls selling fancy foods and coffees, head past the National Kart Centre, and then the Rebel City Distillery – which became the first distillery to open in almost 50 years in Cork in 2020.

There are a couple of fitness clubs before you reach the Marquee tents and the site of Funderland.

All these thriving locations are symbols of what Corkonians now do in their leisure time, and with their spare cash – even the distillery holds walking tours of its premises for the public.

We are a consumer society now, but rewind a generation ago, and Centre Park Road was an entirely different vista.

Along this stretch were the two powerhouses of Cork’s industrial manufacturing landscape for the large part of the 20th century – Dunlop and Ford.

First to go was the tyre company in 1983. And it was 40 years ago today – yes, on Friday the 13th of July, 1984 – that Ford joined it, severing a link granted by the founder Henry Ford – who had ancestral connections to both city and county – that stretched all the way back to 1917.

One of the reasons that Rebel City Distillery has walking tours is because of the history of the site – for it was in that very spot that Ford built cars and tractors for almost 70 years.

******

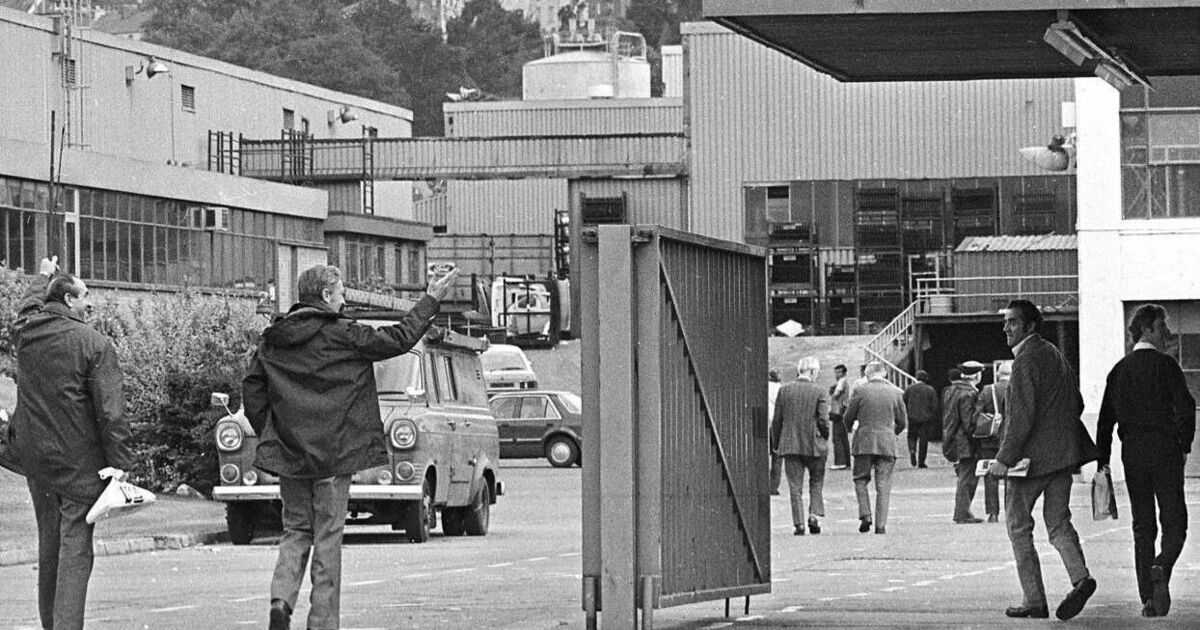

It is hard to grasp now the despair and devastation of that dark day 40 years ago, when 800 workers left the Ford Marina production plant for the last time.

It wasn’t a shock – the closure had been announced in January that year, and there had been rumours of its impending demise for years. The company had lost £8 million in Ireland in 1983, and was expecting similar bad news in 1984.

Ford had been seen as a good employer, providing decent wages, and generations of families had obtained work there.

A job at Ford was a job for life. Money, friendship, self-respect – the plant had provided them all. Now it was gone.

This was an era when manufacturing was dying, not just in Ireland, but elsewhere in Europe; because other parts of the world were doing it cheaper, and technology was replacing humans. New regulations from Ireland joining the European Economic Community (EEC) had also put factories like Ford under pressure.

At the time, the unemployment rate in Ireland was 16%, compared to 4% today, jobs were very scarce, and emigration was seen as the only solution for many workers and families. Cruelly, the workers’ redundancy packages were savagely curbed by a high rate of tax on the pay-offs.

The Lord Mayor in 1984, John Dennehy, whose father and brother worked at Ford, later said, in an interview in 2005: “I don’t think people of that generation after took anything for granted ever again. We realised in the most difficult way possible that nothing lasts forever.”

The tremors from the closure reached out beyond the Ford factory It was estimated that 37 other companies also went out of business in the ripple effect.

The sole bright spot was that Ford would continue to be based in Cork, and would at least maintain a 200-strong workforce. A few years later, it re-located to premises at Boreenmanna Road

The then Cork Examiner on that black Friday, July 13, 1984, tried desperately to lift the mood, splashing on a story about the hope of a new project for Verolme Shipyard that would create 1,000 jobs.

It wasn’t to be, and Verolme itself also closed that year.

The Echo spoke to some of the workers as they arrived at Ford for their last day at 7.30am. One 30-year-old summed up the misery that was unfolding: “There is nothing in Cork for me now. The only option is to get out. Cork is quickly going down the swanee.”

Another, older man said: “If I was a young man, I would emigrate, probably to Australia.”

However, there was defiance too, and some glimmers of hope. One 53-year-old worker vowed he would start his own business with his redundancy package – a craft enterprise.

“What we need here in Ireland is to develop the attitude of self-reliance,” he declared. “We must realise that we have to depend on our own resources and that nobody is going to do things for us. Cork must learn this lesson.”

That man, who had been born in the early 1930s, lest we forget, was showing the spirit and enterprise that would become a hallmark of Cork’s commercial landscape in the years ahead.

It was not clearly identifiable at the time, but the Irish economy was in a state of transition, moving away from heavy industry towards a situation where computer and pharmaceutical companies, for example, would become major job providers.

******

That modern-day walk down Centre Park Road doesn’t contain the ghosts of Cork industry past these days – instead, it offers a snapshot of the progress that has ensured Cork has first survived, then thrived, after the darkest day in its history.

That day in July, 1984, Cork turned for reassurance to a source who had offered it on many occasions in previous years.

Former Taoiseach Jack Lynch, who was born in 1917, the year Ford opened in the city, provided an upbeat vision of the future which ran contrary to the pessimism of the day and was proven prophetic by subsequent events.

“Cork has a reputation for acumen and resilience in the commercial and industrial world. I believe this will be the most important factor in the economic resurgence of the area,” he predicted.

Forty years later, I think the wise old owl had a point, you know.