Fitness

Most Cancer Patients Don’t Receive Recommended Anemia Care

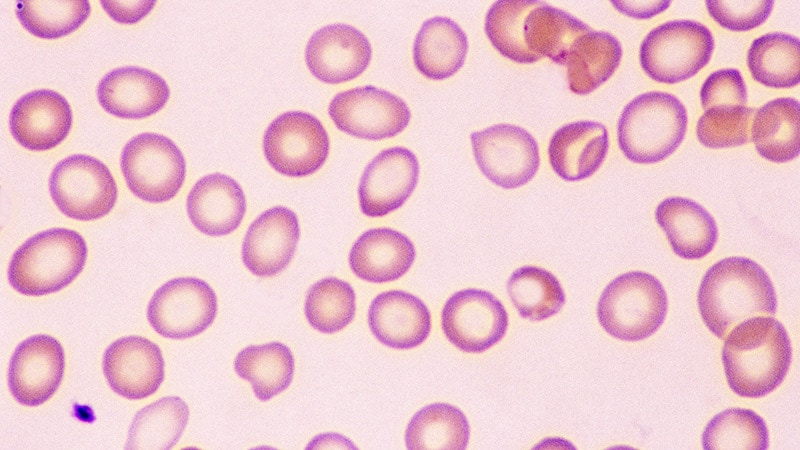

Anemia occurs frequently in patients with cancer, with estimates reaching as high as 90% in those with solid tumors. The red blood cell disorder, which may develop because of tumor-related features or the cancer treatment, can lead to worse quality of life and survival.

Given the prevalence and consequences of anemia in this population, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends routine follow-up evaluations for patients with hemoglobin levels ≤ 11 g/dL.

Research shows, however, that many physicians do not adhere to the NCCN guidelines. Most patients — more than 60% in the US — don’t receive thorough anemia assessments, and even among those who do, fewer than half (about 40%) receive treatment.

Operating Outside the Guidelines

The NCCN guidelines define anemia as a hemoglobin level ≤ 11 g/dL and recommend that patients undergo further workup to determine the cause — an iron or vitamin deficiency or a bone marrow issue, for instance — and best treatment for the condition.

Depending on the cause, treatments may include a blood transfusion, erythropoietin therapy, intravenous or oral iron supplementation, or vitamin B12 or folate supplementation.

“Anemia is a common aspect of oncologic care and is something that should be evaluated and managed as part of a comprehensive cancer program,” Lauren Prescott, MD, MPH, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, told Medscape Medical News.

But a growing body of evidence indicates that is not happening regularly.

Previous research shows that many patients don’t receive adequate anemia testing or treatment. In a 2021 study, for instance, Prescott and colleagues found low rates of compliance with NCCN anemia guidelines among patients with gynecologic cancers: Only one third of patients received NCCN-recommended evaluations for anemia and 42% received treatment.

A more recent retrospective study, published in the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network earlier this year, confirmed high rates of anemia and low rates of follow-up evaluations and treatment in a larger group of patients with solid tumors.

In the 2024 analysis, Prescott and colleagues explored anemia management in a cohort of more than 25,000 patients diagnosed with solid tumors at Vanderbilt University Medical Center between 2008 and 2017. These patients had hemoglobin data available within 6 months of diagnosis. The team tracked whether patients received further tests to identify the cause of and treatment for their anemia and whether patients received treatment, defined as a blood transfusion, intravenous iron, or oral iron.

Among the cohort of 25,018 patients with available hemoglobin data, 44% — just over 11,000 individuals — were anemic within 6 months of their cancer diagnosis. Overall, 3120 patients (28.3%) had mild, or grade 1, anemia; 4686 (42.5%) had moderate, or grade 2, anemia; and 3213 (29.2%) had severe, or grade 3, disease.

However, only 37% of patients received further workup for their anemia; 16% had iron testing and 14% had vitamin B12 or folate tests performed. And fewer than 40% — just 4318 of 11,019 patients with anemia — were treated. Treatments included blood transfusions (32%), oral iron (12%), and intravenous iron supplementation (1%).

The likelihood of receiving treatment for anemia significantly increased with the severity of the condition: 12% among those with grade 1, 31% of those with grade 2, and 77% with grade 3 disease.

The results confirm a high prevalence of anemia in patients with cancer and low compliance with NCCN guidelines for evaluating and treating the condition, the authors concluded.

Findings from another retrospective study, published earlier this year, indicate that issues with anemia testing and treatment are not limited to the US.

Researchers from Germany analyzed data on 1046 patients with cancer and confirmed grade 2 or higher anemia. They found that many patients received inadequate follow-up testing as well as treatments that did not align with current guidelines from the European Society for Medical Oncology and recommendations in Germany. For instance, nearly 60% of patients who did not qualify for red blood cell transfusion on the basis of current guidelines, received a transfusion anyway whereas some patients who qualified for iron or erythropoiesis-stimulating therapies did not receive them.

“Anemia assessment is inadequate, transfusion rates too high, and iron and erythropoietin stimulating agent therapy too infrequent,” first author Hartmut Link, MD, PhD, of the Department of Medicine I, Westpfalz-Klinikum GmbH, Kaiserslautern, Germany, and colleagues concluded.

In Practice, Why Is Anemia Care Subpar?

The collective research underscores shortcomings in adherence to anemia guidelines in cancer across continents.

“There is a pervasive problem of nonadherence to supportive therapy guidelines on an international scale,” explained Link.

Why is this happening?

Just as the causes of anemia in patients with cancer can vary, the reasons many clinicians fail to adequately test and treat patients for the condition also appear to be multifactorial, Prescott said. Although Prescott’s research did not assess the reasons why oncologists failed to adhere to the guidelines, poor uptake of NCCN recommendations probably reflects a lack of awareness, coordination, and documentation.

“Our cohort is a heterogeneous cohort of patients who are often cared for by a combination of surgeons and medical oncologists, and therefore oncologic care is often siloed,” Prescott explained.

The implications of failing to evaluate or treat patients can be serious, Prescott added. Left untreated, anemia may lead to worse survival or affect quality of life.

As Link demonstrated in his study, patients who receive guideline-concordant diagnostics and treatment do better. The researchers found providing appropriate treatment for anemia can improve patients’ quality of life.

Prescott’s team is following up their recent study with a quality improvement initiative to increase compliance at their center, starting with patients who have gynecologic cancers. The results, which are being prepared for publication, show promise for such an initiative, Prescott noted.

But, Link noted, it is not very challenging to adhere to the guidelines.

“Anemia diagnostics is a relatively straightforward process that does not require significant financial investment,” and oncology teams should have regular training on anemia diagnostics and therapy to raise awareness of the problem and simple solutions, Link said.

The authors had no disclosures to report. Link’s disclosures include funding, research, or consulting relationships with Pharmacosmos and Teva.