Cricket

As cricket begins American Dream, hopes, doubts on changing traditions

LIKE MILLIONS of immigrants in the US, Chuck Ramkissoon, the central figure of Joseph O’Neill’s best-selling novel Netherland, wanted to live the American Dream. He did odd jobs to survive while, all along, not taking his eyes off his dream — of becoming a millionaire by making cricket great again. “Cricket was the first modern team sport in America,” he tells his friend and the novel’s protagonist, Hansvan den Broek.

With similar ambitions of harnessing the world’s most powerful sports market, something cricket has failed to do so far, the men’s T20 World Cup arrives in the United States on June 2.

Sunday,the home team is set to play Canada in the opening game, but it is the other neighbourly clash, India vs Pakistan on, June 9 in New York, that is expected to turn the global gaze on cricket in America. After 16 group games in the US, the action moves to the West Indies, with the final in Barbados on June 29.

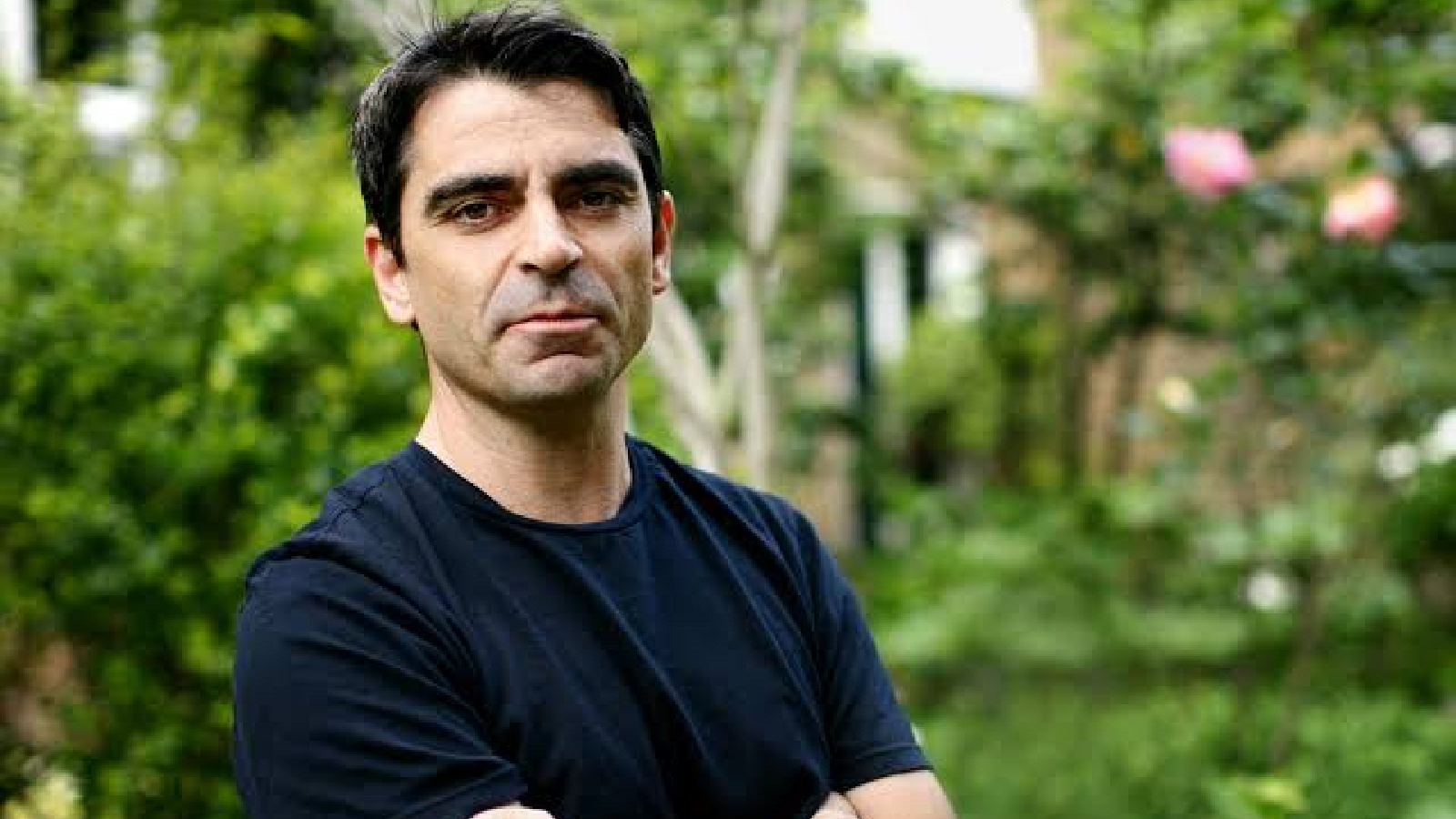

O’Neill has played cricket in the country of his birth, Ireland, age-group cricket in Holland where he spent his childhood, in England where he did his higher studies, and in New York, where he is living. And he knows the importance of this World T20.

“I would love cricket to become big in the States. This World Cup has a great format, with true global participation. It will be very appreciated by the large US cricket community,” says the writer, whose 2008 cricket novel was compared to The Great Gatsby by The New Yorker book critic James Wood, one of the most revered voices in literary review.

But “will its park cricket to life in the USA? I’m not so sure”, he says. “The grassroots of the game needs more sustained investment to make that happen.”

Referring to Chuck’s dream of building a stadium where the greats of the game would play, O’Neill says: “What was Chuck’s biggest dream? It was to build a world-class stadium in New York. Sixteen years later (after Netherland was published), New York doesn’t have one. There are just a few in the whole country. You need to build a lot of grounds in the country to make the sport big, and make it a sport in college.”

Indeed. For instance, two of India’s games during the T20 World Cup would be held in a make shift stadium at Long Island. The plan was to transform Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx to a cricket stadium, but it was shelved due to staunch public rage. “Now who does that, converting a neighbourhood park into a cricket stadium? It (the park) is so much apart of American life,” says O’Neill.

Though the men’s T20 World Cup will be the first big international cricket tournament in the US, the sport is no stranger to the country with a large immigrant community, including from South Asia where cricket fuels passions. In summers, several parks in the US change into cricket pitches as communities blend into each other’s lives for the game. As Chuck muses in the novel, “Every summer the parks of this city are taken over by hundreds of cricketers, but somehow nobody notices. It’s like we’re invisible.”

It’s the piece of land, the pitch, that binds Chuck and Hans, and fuels Chuck’s dream. “What’s the first thing that happens when Pakistan and India make peace?” says Chuck in one passage,”They play a cricket match.”

“Cricket is instructive, Hans. It has a moral angle… I say, we want to have something in common with Hindus and Muslims?

Chuck Ramkissoon is going to make it happen. With the New York Cricket Club, we could start a whole new chapter in US history. Why not?” the passage goes on.

In real life, O’Neill admits cricket has at ranscending, unifyingforce. “Yeah, I mean there is a lot of what I have seen and experienced in New York, especially when I played the game.It brings together people who would not have mingled otherwise, like Jamaicans and Indians, those from Guyana and Bangladesh,” he says.

Like the Staten Island Club in NewYork, the club O’Neill played for and is the vice-president now, with a 95-year-old Trinidadian its president and many Indians in the committee. The sport’s fabled prowess to bind different communities and cultures may have sparked the ICC’s American dreams, but, says O’Neill, things are not easy.

“You can change the character of a country, it keeps changing all the time when you perceive things closely. But to change traditions is difficult, especially sporting traditions. It’s something like a family heritage, passed on from one father to children, and down the generations,”he says.

For instance, he says, there is little buzz about the World Cup outside the traditional cricketing communities in the US. “It is like a global game has reached here, but there is no local connect. The tickets are sold globally, and the tickets are pricey and out of the reach of the locals. I don’t know if it is affordable for even all of the South Asians, like those who drive taxis and run shops. The number of immigrants has doubled, but the income has not for everyone.”

The writer himself has managed only a couple of tickets for the Ireland games, because the rest were “too expensive”.

“Ideally,” he says, “a few tickets should be kept aside for the local clubs. The clubs should auction it, and investthe money from the proceeds into the grassroots.”

“It’s the only way you could develop the sport in the country. You could take the example of American Football, now the most popular sport in the country. It’s there in school, high school and college,” says the writer, whose latest novel, Godwin, is premised around football.

But the World Cup could be the one short step that could turn out to be one big leap for the game.