Fitness

Cardiometabolic Diseases Threaten Life Expectancy Gains, Even In Young Countries – Health Policy Watch

GENEVA – Cardiometabolic diseases, a group of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, are on the rise globally, threatening life expectancy gains and burdening vulnerable economies with excess healthcare costs.

These diseases already contribute to over 30% of global deaths each year. With one billion people now living with obesity, projections suggest that by 2035, 50% of the world’s population will be affected, leading to premature deaths and a growing economic burden.

“Non-communicable diseases are only going in one direction. They are increasing,” Dr Christopher Tufton, Jamaican Minister of Health, remarked at a World Heart Federation (WHF) and World Obesity Federation (WOF) event in Geneva on Monday. “It is at a catastrophic level and it concerns all of us wherever we are.”

Low- and middle-income countries, despite their relatively young populations, are driving the alarming rise in global obesity. Obesity rates in these countries are expected to soon match those in high-income countries, a significant shift from the trend observed just a decade ago, said Francesco Branca, director of the Department of Nutrition and Food Safety at the World Health Organization.

Cardiometabolic diseases pose a particularly severe threat to low- and middle-income countries, not only jeopardizing hard-fought life expectancy gains but also burdening their already fragile economies with excessive healthcare costs, threatening the sustainability of their health systems and diverting funds from other crucial areas of healthcare.

“The data suggests that we’re seeing a reversal of the gains that we’ve made in life expectancy,” Tufton said, highlighting the impact on his home country Jamaica. “The opportunities to live up to an average of 75 years is now under serious threat.”

In 2020, non-communicable diseases accounted for 77% of all deaths in Jamaica, with age-standardized mortality rates showing significant increases in deaths from diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease over the past decade.

Rise of cardiometabolic diseases in children and adolescents, fueled by targeted advertising

The increased rate of deaths from cardiometabolic diseases in countries like Jamaica is not solely a result of an ageing population, but rather an incremental rise in deaths across all age groups, including children and adolescents.

Dr Monika Arora, Vice President of Research and Health Promotion at the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), argued that much of the reason for the rise of obesity in younger children stems from advertising and hidden additives.

“Advertisements for foods high in fat, salt, and sugar — the exposure was much higher in children’s [TV] channels than young adult channels, meaning the industry very clearly wants them to be hooked on to their products early on,” she said.

India, a country that struggles with both undernutrition and overnutrition, now has the third-highest prevalence of obesity globally, largely due to aggressive advertising targeting children and the rise of ultra-processed foods (UPF). The urban poor are the hardest hit, as cheap food options often come in the form of ultra-processed foods, while fresh fruits and vegetables remain too costly.

“They don’t have any means for physical activity, and they don’t have food which is healthy and cost-effective,” said Arora. Urban air pollution further compounds the barriers to exercise, as the air quality is often too dangerous for walking or running outdoors, she added in an interview with Health Policy Watch.

Ultra-processed foods may also be “hidden,” for example, the additives in milk products advertised as being for children.

“There’s a whole culture about feeding children milk. The milk additives are claiming 20% better growth, better height, and better immunity, and nobody’s checking where these studies are published — these are filled with high-sugar products. These are all hidden calories. So even in urban settings where people are cutting down on sugar, they don’t realize that these are ultra-processed foods, and they continue to feed children with products that are harmful.”

The long-term consequences of childhood obesity and the predatory tactics that fuel it are staggering for individuals and health systems alike. A 2015 National Institutes of Health study of over 200,000 U.S. children found that obese children and adolescents were nearly five times more likely to be obese as adults compared to their non-obese peers. The study showed that 55% of obese children become obese adolescents, 80% of obese adolescents remain obese in adulthood, and 70% will continue to be obese beyond age 30.

“These young people are going to have a life-long exposure to this condition,” Branca warned.

Growing economic burdens globally

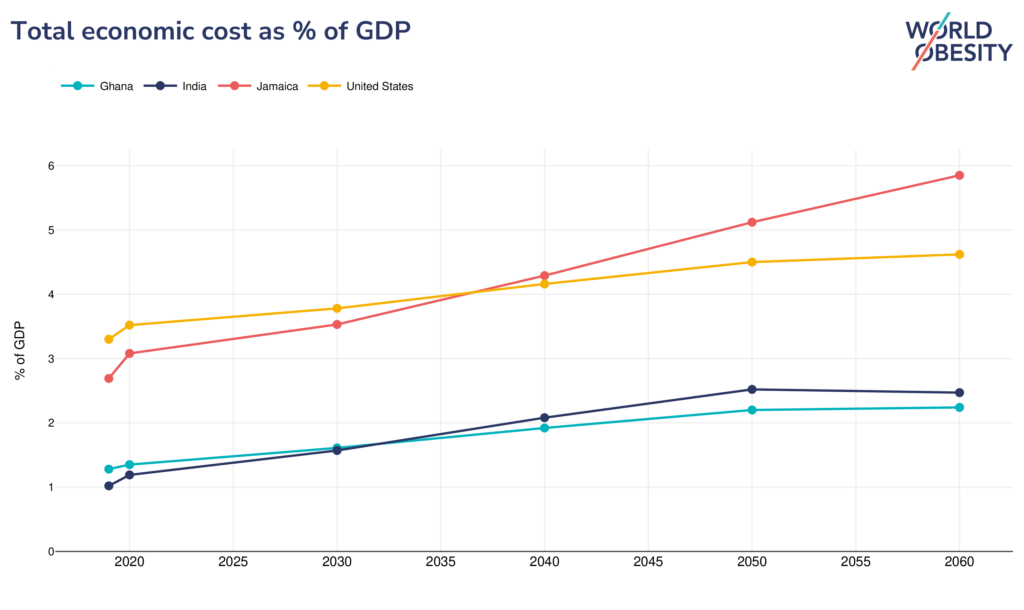

As more low- and middle-income countries struggle with obesity and other cardiometabolic diseases, the economic impact of these conditions continues to grow.

In Jamaica, for example, the total economic impact of obesity is projected to reach $524 million by 2025, with the burden on GDP expected to be 3.9% by 2035, according to Tufton.

The global economic impact of overweight and obesity will reach $4.32 trillion annually by 2035 if prevention and treatment measures do not improve, according to the World Obesity Federation’s World Obesity Atlas 2023. The report notes that at almost 3% of global GDP, this impact is “comparable to that of COVID-19 in 2020.”

However, the Obesity Atlas only tracks direct costs. When accounting for the knock-on social, economic, and health costs resulting from obesity, its true cost to society at large doubles.

“It’s also about framing the societal value for patients, healthcare systems, and economies of taking action and avoiding those costs, which for obesity alone is estimated to be $4 trillion if we don’t take action,” said Jo Jewell, Novo Nordisk Director of Cities for Better Health & Head of Obesity Health Equity.

Comprehensive prevention, treatment, and management are crucial, Jewell noted, with partnerships between the private sector, healthcare sector, and governments to reach those most in need within communities.

Basic screening for conditions like hypertension, blood pressure, and diabetes is essential, and governments should work to bring screening to the people, Tufton added. Knowing these numbers provides a basis for healthcare providers to give meaningful advice and “encourage” behaviour change.

“It is about taking screening to the people,” Tufton said, “as opposed to encouraging people to come to the health centres or the clinics or your private practitioners to get screening.”

“Children live what they learn”

Government policies targeting individual behaviour are a core component of plans to tackle the obesity epidemic. However, reflecting on the power of targeted advertising and hidden additives in ultra-processed foods, Branca noted that individuals are not solely responsible for obesity. This marks a paradigm shift in how the disease is perceived, as an individual’s obesity was previously viewed predominantly as a personal failing.

Policies that only target individual behaviours alone are “clearly” not sufficient, Branca said, and must be paired with policies that create environments allowing people to make healthy choices, such as controlling marketing, eliminating trans fats, and lowering food prices.

This approach extends to helping children make good decisions about nutrition from early childhood onward. The “captive environment” of schools and the educational programs they provide have the potential to influence community-level change through nutrition and exercise initiatives, multiple experts on the panel noted.

The success of these childhood education programs depends on working closely with school authorities to provide a supportive environment, including less unhealthy food, physical education, and empowerment to make healthy food choices.

“When we work with children in school settings, we are definitely able to influence their behaviours, whether it is healthy eating and being more physically active,” said Arora. She added that including children and young adults in decision-making plans around nutrition is key to ensuring “sustainable behaviour” and empowers them not to “go back home and resort to unhealthy food.”

“We believe that our youngsters could be great teachers of the adults by making an impression on them in schools,” Tufton added. “If we were to modify what they consume, and encourage them to consume in a more balanced way, combined with physical activity, then they will grow hopefully to follow that pattern and become a healthier adult over time.”

Image Credits: S. Samantaroy/HPW, World Obesity Federation.

Combat the infodemic in health information and support health policy reporting from the global South. Our growing network of journalists in Africa, Asia, Geneva and New York connect the dots between regional realities and the big global debates, with evidence-based, open access news and analysis. To make a personal or organisational contribution click here on PayPal.