Tennis

Game, Set, Match: Tennis Terror in When No One Was Looking and Win, Lose or Die – Reactor

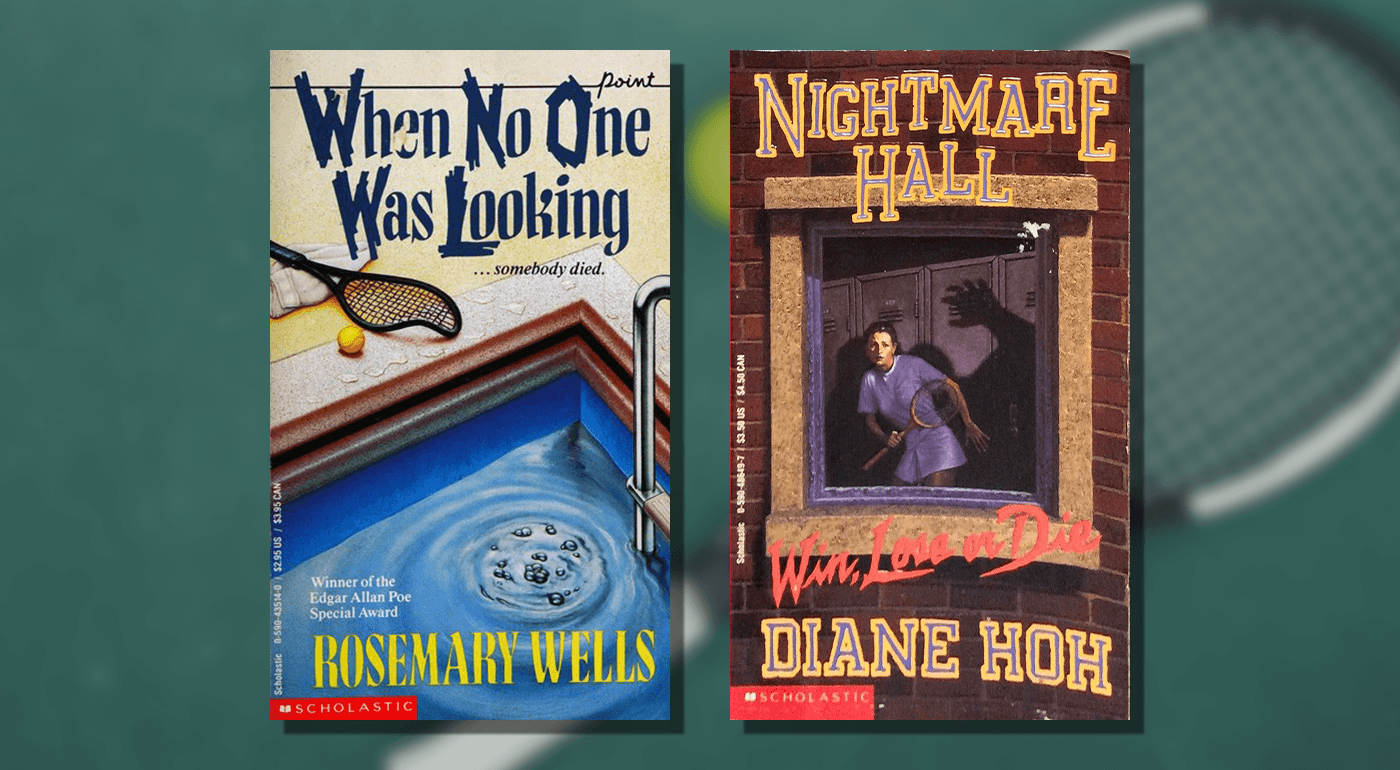

There are a handful of teen horror covers that I can still picture vividly decades later, the memory of which evoke a specific moment in time and in my life, grounding me once more in my middle school library or the local mall bookstore. Christopher Pike’s The Midnight Club. R.L. Stine’s The Babysitter. Richie Tankersley Cusick’s Trick or Treat. One of the covers that remains memorable from that time is When No One Was Looking by Rosemary Wells, with its ominously dented tennis racket beside a blue pool with a cluster of bubbles rising to the surface. It’s a clear, focused image and tells a seemingly straightforward story: someone got whacked with a tennis racket and has drowned (or is drowning—with the frozen state of the bubbles, it’s hard to tell. Are they still rising? Are these the last few?) And in case there was any uncertainty, the memorable tagline (“… somebody died”) clears that up with a cursory glance. So you can imagine my surprise when I picked this book up again after all these years and found that while it was republished by Scholastic in 1991, presumably to cash in on the early days of the teen paperback horror trend, it was originally published in 1980.

This realization presented a fascinating rabbit hole of exploration, including the novel’s different covers over the years, which range from a soft-focus teen problem-style illustration of a conflicted girl staring wistfully off into the middle distance to more shadowy, to brooding covers featuring some combination of pools, a tennis racket, and tennis balls, underscoring the mystery elements of the story with a cover note on the novel’s Edgar Allan Poe Special Award. When No One Was Looking offers a fascinating case study all its own, in considering the different marketing strategies and cover designs that indicate the range of ways in which the book appealed to readers with varying expectations in disparate cultural contexts. In considering it within the context of 1990s teen horror novels—a position which is complex and somewhat contentious—it also serves as an interesting parallel to Diane Hoh’s Nightmare Hall book Win, Lose or Die (1994).

Both books focus on young, competitive female tennis players and present some of the darker sides of competition and driven young athletes, but their approaches are very different and only Hoh’s is really at home in this ‘90s teen horror context. While the cover of When No One Was Looking was redesigned for its 1991 Scholastic republication to catch the eye—and disposable income—of teen horror readers and I’m sure that fans of Hoh, Stine, and Pike read it within that context, the story has a completely different style, more understated and internally-focused than those ‘90s books. While I could vividly recall the cover imagery all these years later, I soon realized that I had absolutely no memory of the story itself. It’s not necessarily better or worse than those other books, but it’s definitely a different kind of story, seemingly shoehorned into the Point Horror aesthetic to capitalize on the trend.

In When No One Was Looking, Kathy Bardy is a fourteen-year-old tennis phenom. She practices relentlessly, has a part-time job at the local country club to help offset the cost of her membership to access the courts, and has an award-winning coach named Marty, whose no-nonsense, tough love approach skirts right up to the line of abusive (and arguably sometimes crosses it). Kathy was “discovered” at a tennis clinic a couple of years prior, when she was just hitting the ball around for something fun to do, and now she seems on pace to win the Junior Championship and even potentially go pro in just a few short years. She’s got innate talent and the drive to work hard to hone her skills … and she’s also got a ferocious temper. She beats just about everybody, until she goes up against Ruth Gumm, a new girl in town, who is a bit clumsy, round-faced with a bad complexion, and impossible for Kathy to win against. When she plays Ruth, Kathy always makes mistakes and loses her cool, and her stress level spikes when she finds out she has to play Ruth in a tournament to secure her spot in the national competition. With everything on the line, Kathy’s not sure she can win, though she never has to find out, because just before the tournament, Ruth turns up dead in the club pool. Everyone tells Kathy it was a tragic accident, to keep her mind on tennis, and just keep winning, but Kathy can’t help wondering whether someone close to her murdered Ruth to clear her path to greatness, which then cascades into her questioning her own ability, the stakes of her success, and whether she even really likes tennis at all.

Everything is riding on Kathy’s success: her working-class family has put all of their resources into Kathy’s tennis, including drastic budget-cutting measures like moving Kathy’s grandma from a decent (though not exactly great) nursing home to a pretty terrible one. The whole family makes sacrifices and their lives all revolve around tennis, as they accompany Kathy to tournament after tournament, study her opponents so they can brief her between matches, and drag Kathy’s less tennis-enthused younger sister and brother along for the ride. (The Bardy family’s lack is cast in even starker relief by Kathy’s constant comparison of their lives with that of her best friend Julia Redmond and her family, who are incredibly wealthy, have servants, and jet off on European vacations.) Kathy’s hometown has similarly high expectations of her and people are willing to bend the rules to a horrifying degree to ensure she succeeds and makes them all look good: the superintendent of her school sets things up so that Kathy can cheat on her Algebra test and pass the class, while the chief of police overlooks any evidence that might point to foul play in Ruth’s death, in order to protect Kathy. There’s also Oliver, who claims to be a freshman at Yale University and takes a quasi-romantic interest in Kathy, though it’s never clear whether his intentions are friendly or predatory (or even who he really is, as there are conflicting rumors and speculation). Either way, a college freshman obsessively hanging around a fourteen year old girl is really unsettling, particularly as he insinuates himself into Kathy’s life and family. The Bardys, her coach, and Kathy’s community are all making a serious investment in Kathy, one that they expect she will someday repay by improving all of their lives when she makes it big and goes pro. It’s all riding on Kathy, so when she’s worried about her mental health, thinking about quitting tennis, and would rather be playing baseball, no one really cares. Their advice is simple and non-negotiable: get back out there, hit the practice courts, and win. No excuses, no exceptions.

In Hoh’s Win, Lose or Die, Nicki Bedsoe is a freshman in college and has a bit more agency and control over her choices, though tennis is an overwhelming influence in her life as well. Like Kathy, Nicki spent her adolescence competing in tournament after tournament, and like Kathy, Nicki also had a temper she had some trouble controlling, throwing a racket after a particularly challenging loss when she was twelve years old. Despite these stresses, tennis was a lifeline throughout Nicki’s childhood: her father was in the military and her family moved around a lot when she was growing up, which made tennis an essential core part of her identity, and key to her acceptance in new places, as she could always find a social group with her fellow players, as long as she was good enough to bring something vital to the team and help them win. At the beginning of Win, Lose or Die, Nicki gets recruited by the Salem University tennis coach and transfers there from a larger state college, drawn by the full academic scholarship the coach offers her, which is an economic necessity that Nicki can’t turn down.

Competition among the Salem University tennis team is high and Nicki is not welcomed with open arms, especially by team superstar Libby DeVoe. While the tensions originally start as typical mean girl antics, things quickly become more dangerous and even deadly, when Barb, one of Nicki’s teammates, is electrocuted in a whirlpool “accident” intended for Nicki, and someone fills one of Nicki’s tennis balls with red paint and paint thinner, in an attempt to sabotage and blind her. Nicki can’t figure out why someone would want to hurt or kill her, until she finds out a dark secret about her own past: when she hurled that tennis racket in a fit of temper six years ago, a piece of flying gravel flew up and injured another kid, blinding him in one eye and ending his tennis career. Her parents paid for all of the child’s medical expenses but never told Nicki, and because their family moved right after the tournament, she never saw it on the news or heard about it from anyone else, until some of her teammates at Salem remember and talk about the tournament (though they don’t know she’s the one who threw the racket). While Nicki has been suspicious of and on guard against her tennis teammates since arriving at Salem, with this revelation, she now becomes leery of anyone who isn’t a tennis player, which means she can’t trust anyone at all.

In both When No One Was Looking and Win, Lose or Die, it seems like literally everyone is a suspect. While the public message is that Ruth Gumm’s death was a tragic accident, when Ruth’s parents insist on an investigation, the police (begrudgingly) work to figure out where Kathy, her parents, her coach, and even her little sister were at when Ruth died. The only potential clue is some clay that was tracked into the pool area, which seems to place the suspected murderer at the tennis tournament before they came to take Ruth out of the picture, and those in Kathy’s orbit seem to be the people with the strongest motives. Similarly, in Win, Lose or Die, the suspect list is long and complicated: some of Nicki’s tennis teammates could potentially want to hurt her, either out of jealousy or to gain a competitive edge by driving her off the team or eliminating her. The mystery child Nicki accidentally blinded has a clear motive for revenge. Outside of tennis, Nicki makes friends with Deacon and Mel, two fellow students known for getting into trouble, with misdeeds that range from spiking the sloppy joes at a fraternity party with a whole lot of hot sauce to shoplifting.

Kathy and Nicki are both left with no one they can trust and few people they can talk to, with the exception of an intimate inner circle of trusted friends—in Kathy’s case, this is her wealthy best friend Julia, while Nicki turns to Pat and Ginnie, the only two teammates at Salem who have welcomed her with kindness and open arms. Both girls’ lives shrink down to these insular safe spaces with just a trusted friend or two, which makes it even more devastating when they find out that these are the very people responsible for the horrors they have encountered. In When No One Was Looking, Kathy realizes that Julia is the culprit when the police chief tells her that they have officially ruled Ruth’s death an accident and eliminated all tennis-related suspects, because the material found at the pool wasn’t clay after all, but a special type of art plaster that only Kathy knows Julia had access to. There’s no clear motivation provided and Kathy never asks Julia about it, so readers don’t get to hear her side of the story. Instead, in the book’s final pages, Kathy is nearly incapacitated by this realization, thinking to herself “Ruth is dead, in part because of you … Julia has to live with what happened, and as much as your connection to it is as thin as a spider’s thread, it is part of your life now too” (217). Kathy contemplates quitting tennis altogether, but finds herself thinking even more about Julia and how “Giving her up would be infinitely trickier than throwing a racket into the sea” (218). In Win, Lose or Die, Nicki finds the mystery kid she accidentally blinded, though he turns out to be a fellow student and all around nice guy named Jon, who harbors her no ill will. Tennis is still at the heart of the conflict, however, as Nicki finds out that the full scholarship the coach offered her was taken away from someone else: Nicki’s friend Pat, who is willing to kill Nicki to make her pay for what Pat has lost.

There are some resonant themes between When No One Was Looking and Win, Lose or Die, including cutthroat competition, economic inequity, and the pressure put on high-achieving young athletes. But they also each clearly reflect their specific moment and genre context. When No One Was Looking is just as invested in the conflicts and desires of the adult characters as it is in Kathy’s, while in true teen horror fashion, the students of Salem University are a world unto themselves in Win, Lose or Die. When No One Was Looking is a mystery rather than a horror story, and the mystery is bifurcated between who killed Ruth Gumm and how Kathy will choose to define herself. It’s a coming-of-age story that is ultimately unresolved. Kathy has been transformed by her experience of and proximity to Ruth’s death, even doubting herself and how others see her. She could keep playing tennis or quit. She could stay friends with Julia or cut her out of her life completely. Any of these choices seem possible, though none of them will change what happened or give Kathy back the life or innocence she had before. In contrast, Win, Lose or Die is much more action-oriented: terrifying things happen, while Nicki tries to figure out why they’re happening, who’s doing it, and how to stay alive. There is definitely some internal growth and self-reflection, particularly when she learns about the child she blinded, but the main focus of the story and its conflict is much more externally-focused that that of When No One Was Looking. And unlike Kathy, in the end, Nicki’s life pretty much goes back to normal, as in the book’s final pages, Nicki realizes that she and her friends had “put the whole horrible business behind them … Exactly where it belonged” (209).

There is an insularity and repetition in ‘90s teen horror paperbacks, where everything is set relatively right at the story’s end, reset so it can go horrifically wrong all over again in the next installment, a nightmare of Sisyphean proportions. But in the end, that still might be easier than the existential crisis Kathy’s left holding at the end of When No One Was Looking, where nothing can go back to the way it once was and some of the horrors still wait around the next corner.