“And all the people said, ‘What a shame that he’s dead.’ But wasn’t he a most peculiar man?” —Paul Simon

He was my first. David Hofmans was the first person this reporter interviewed for a story for which I would be paid good American dollars. I described him as “bright, balding, and in shameless love with his work.” He was fresh from his second season as a public trainer, during which his horses earned all of $226,598. I was 25, Hofmans was 32. And now I must write of his death.

But that’s for later.

Denk: Classic-Winning Trainer David Hofmans Dies at 81

David Eugene Hofmans was a most peculiar man, but peculiar in a way that made you stop, and wonder, and always want to know more. He stood out, even by the eccentric standards of the Thoroughbred racing world, described by his daughter, Jill Hofmans, as “that cozy ecosystem of horses and loyal help, friends and congenial competitors, expertise and alchemy, ego and self-worth.”

“He was a man of the people, and on the surface, he was ever-smiling and upbeat,” said Jill, executive director of the Conway Center for Family Business in Columbus, Ohio. “He was much more complicated than that.”

Complicated seems to be a vital requisite for the job. The Thoroughbred trainer, if he is any good at all, embodies F. Scott Fitzgerald’s reminder that “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

Hofmans and Touch Gold

“I don’t know what to think,” Hofmans said the day Touch Gold worked seven-eighths in 1:23 4/5 on a repaired foot one week before the 1997 Belmont Stakes (G1), “except that it was too fast and he did it easy.”

No wonder trainers have mastered any number of coping mechanisms. Richard Mandella deflects by cracking wise. Todd Pletcher dips into a handy basket of safe sound bites. Bill Mott will go quiet, stare at a spot off in space, then 10 minutes later answer your question, long after you’ve forgotten what you asked. Dave Hofmans grinned and made you laugh.

Is it blasphemous to lump Hofmans in with such Hall of Fame names, in any regard? Not hardly. His record stands scrutiny from all angles, and the privilege of being there for many of his greatest moments was priceless.

The day after he sent forth Touch Gold to end the Triple Crown dreams of Silver Charm in the 1997 Belmont Stakes, Hofmans made his way unrecognized through the lobby of the Garden City Hotel, bemused by his anonymity while concerned for his young star.

“I don’t think my colt is getting the recognition he deserves,” Hofmans said as he emerged into the Long Island morning. “And I understand that. It’s a big letdown for the fans and the game. But people should realize just what a big race he ran. And what a great horse he could be.”

There was that golden autumn evening in Canada, back at the barn after Hofmans, Chris McCarron, and Alphabet Soup had spoiled Cigar’s day in the 1996 Breeders’ Cup Classic (G1) at Woodbine. The trainer lavished attention on his other Classic runner, Dramatic Gold, then turned to the slender gray horse with the black-rimmed eyes.

“Look at him, the little devil,” Hofmans said as he touched Alphabet Soup. “Did you see the way he pinned his ears and set his jaw when Cigar came to him? Cigar! And he wasn’t about to let him by.”

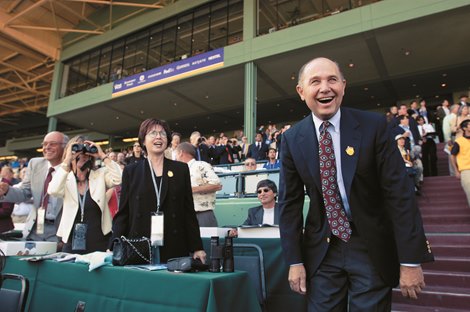

Hofmans at the 2003 Breeders’ Cup

Two more Breeders’ Cup wins followed—Adoration at 40-1 and Desert Code at 36-1—both dizzying delights that came early on their programs, allowing Hofmans to float through the rest of the day. More recently, there was the 2016 Santa Anita Handicap (G1) won by a gelding who had spent a year on the sidelines recuperating from equine protozoal myeloencephalitis, otherwise known as EPM. His name was Melatonin , and that was Hofmans attending to his wheelchair-bound owner, Susan Osborne, as they made their way carefully, joyfully to the winner’s circle.

The names of the other major Hofmans horses might not sound instantly familiar bells, but the major races they won ring loud and clear: the Blue Grass Stakes (G1), the Acorn Stakes (G1), the Meadowlands Cup Handicap (G1), the Santa Margarita Invitational Handicap (G1), the Bing Crosby Handicap (G1), the Haskell Invitational Handicap (G1), the Hollywood Derby (G1T), and Del Mar Futurity (G1). Toss in a Queen’s Plate as well, for a prime Canadian double. But if Hofmans were asked to hang his reputation on a single horse, he would think first of Alphabet Soup and then land squarely on His Legacy, a California-bred son of Pocketful in Vail owned by Pete Parella’s Legacy Ranch. His Legacy raced until age 9, after seven years with the Hofmans barn, with 14 wins, 17 seconds and thirds, and a victorious last hurrah.

“I remember his final race, the Cal Cup at Santa Anita,” Hofmans told Ed Golden in Trainer Magazine. “My son and I were standing as he came down the stretch, both crying we were so emotional.”

Hofmans doted on his three children from his first marriage—Grant, Jill, and Amy—and six grandchildren. Hofmans and his wife, Linda, were married in 2012 after meeting on a blind date arranged by a mutual friend.

Grant Hofmans served as assistant to his father for 11 years. He currently is the manager of the Diamond A Farm branch of the Taylor Made Farm operation in Kentucky.

“Patience,” Grant said when asked what made his father a superb trainer. “You know how kind he was with people, and he was that way with the horses. He just loved them. And when he put a jock on a horse, that jock knew the horse was in the best condition and the best health he could be.”

Hofmans

Training Thoroughbreds is a game of life and sometimes death. David Hofmans was scarred early by a serious injury to his first good horse, the 1975 Graduation Stakes winner Lexington Laugh, who eventually foundered and was euthanized. Years later, during a spate of breakdowns experienced by other stables, Hofmans articulated the grim reality that few are willing to utter aloud.

“This business is built on the broken bones of these horses,” Hofmans said. “We can never forget that.”

He never did, but neither did he apologize for his chosen profession.

“We know it can no longer be said that fatalities are ‘part of the game,'” Hofmans said a few years ago when scrutiny on trainers was increasing. “No one should accept that. And yet it makes no sense that a trainer would intentionally put a horse out there they know is in obvious jeopardy. I’m not naïve enough to think that there aren’t trainers who take such chances. But for the great majority of us, there is a tremendous cost to losing a horse, both emotionally and economically.”

The Hofmans barn, even at its 40-horse peak, was an island of relative serenity in a stormy world.

“The way my dad did it, you would never know how good he was,” Grant Hofmans said. “He was always out there…telling stories and making everybody laugh. Back at the barn he was all business, but without any yelling or screaming. He let me and the other employees do our thing, while he’d be watching in that patient way, and step in when he needed to. He guided in a kind way, and the help loved him. And he always made time for everybody. It would drive me nuts. ‘Let’s go, dad. We’ve got to get the set out.’ Then it was screw it, we’ll go without you.”

Sometimes, the famous Hofmans equanimity could be frustrating.

“Right? I’m his son, and it would piss me off,” said Grant, more than half serious. “‘Come on, man. Get mad. You just got beat!’ Here I am, a spoiled brat kid stomping around and he’d be, ‘Take it easy. It’s okay.’ That doesn’t mean he wasn’t very competitive. He was. But it was never anyone’s fault when we got beat, unless he thought it was his.”

Hofmans died July 3, after one last call to his Santa Anita Park barn foreman, Seledonio “Chololo” Cano, telling him to simply walk the horses that morning and he would be there soon. Hofmans was found at home, the cause of death was self-inflicted asphyxiation, and the requirement of an official autopsy followed.

Glowing encomiums from industry colleagues have flowed, accompanied by the persistent drip-drip of the accompanying question: Why would he end his own life?

Despite his proven ability to plumb the depths of whatever talent a horse might display, Hofmans experienced down years amidst the bounty provided by those major stakes winners. At one point, he battled, successfully, a blood disorder that diverted his attention. Close friends and family conceded that he was prone to periodic bouts of depression. At the time of his death, he was training just six horses, none of them of apparent stakes quality. His last starter was June 2, while the last of his 1,085 winners came May 11.

At the end of the day, such questions of ‘why’ default to Albert Camus, the captain of Team Existential, who wrote, “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.”

In his role as vice president of the California Thoroughbred Trainers, it was apparent Hofmans still cared very much about the game. Conversely, the game didn’t care very much for him. His stalls contained a couple of token horses from long-standing clients, but for the most part, his skills were being squandered because the birthdate on his driver’s license read Jan. 27, 1943.

“We talked about it a lot,” Grant said. “He had clients giving horses to younger trainers, while he was still winning races for them, and that really bothered him. I’d say, ‘You’re 81 on the number, but you feel like 60, I know.’ I told him he had to change to compete for horses with the young guys—get on social media, get an Instagram account, throw stuff out there—that’s what these guys are doing, running around with an iPad instead of a Racing Form.”

Not surprisingly, Hofmans resisted the idea of becoming a blue check on Twitter/X.

“I talked to him last Sunday,” Grant said. “We talked about the game. He (was upset) about the stall app for Del Mar—the usual stuff. He said, ‘I gotta just retire. I’ve gotta get out of here.'”

What Hofmans meant by that, his son can only guess.

“We’re all trying to make sense of this tragedy,” Jill Hofmans said. “How a very hale and hearty man, although 81, is no longer with us. Who knows if it was the reality of crippling economic woes, outside pressure to give it up, or the ever-advancing march toward failing health. We still thought, as most do, that we had more time.

“Suicide has such a sting to it, and yet for him it made sense,” she added. “He was the most selfless man in life. I loved him ferociously. He is at peace now, and I take a bit of pleasure in feeling that his last act was one of his only selfish ones and, frankly, quite brave. I respect him for that.”

If Dave Hofmans ever read anything by Arthur Schopenhauer, something the German philosopher wrote would have made perfect sense:

“When a man destroys his existence as an individual, he is not by any means destroying his will to live. On the contrary, he would like to live if he could do so with satisfaction to himself, if he could assert his will against the power of circumstance. But circumstance is too strong for him.”

“Racing made him who he was,” Grant said. “Without the business, without the horses, he had nothing. And if he retired, what was next? Getting older, getting sick? He never would have handled that, being a burden. My dad was the caretaker.

“He talked about it, and he was never afraid of it, of death,” Grant added. “I guess he just wanted it to be on his terms, and I don’t blame him. We loved each other very much, and we both knew it. We talked a lot, it wasn’t always about horses, and every conversation ended with ‘I love you.'”