Entertainment

Love, lust and mystery in Victorian Dublin: fascinating diary shines a light on shadowy woman caught up in illicit affair

A diary about sex, love and desire is gold dust for historians seeking stories about the past

Sometime around 2010, I came across the diary of James Christopher Kenney in the archives at Trinity College Dublin.

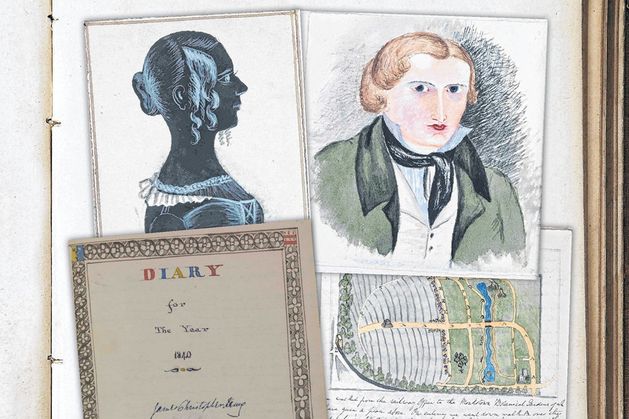

Self portrait in diary of James Christopher Kenney

At first the diary, recorded in 1840 and 1841, wasn’t that interesting. James lived a privileged but ordinary life — riding, hunting, reading and occasionally studying. But then he met Mary Louisa McMahon and I was glued to the page.

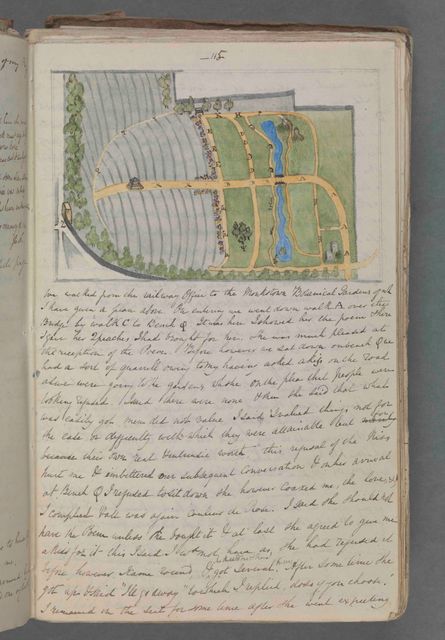

Mary was a lady’s companion for James’s grandmother when he fell in love with her. In meticulous detail he recorded his longings, their meetings and his attempts to gain her affection. He even drew maps of the parks they met in, labelling locations where he attempted to kiss her or where he declared his love.

On a page after his hand-drawn map of St Stephen’s Green he wrote that on “bench 2… we had a sort of quarrel & I left her going out at gate F however I came back in a few moments”.

Their courtship was an elaborate dance in semi-public spaces: St Stephen’s Green, Merrion Square and the Monkstown Botanic Gardens. They even hung out in a cemetery. They cuddled — Mary sat on James’s knee, James rested his head against her breast, James “pressed her loving heart”, he kissed her hand, her lips. Sometimes, he thought, she kissed back.

Occasionally they had an audience. In Monkstown, James recorded that “some brats annoyed us who cried out, having seen me kiss her, ‘give her another’”. James defended Mary by throwing stones at the children.

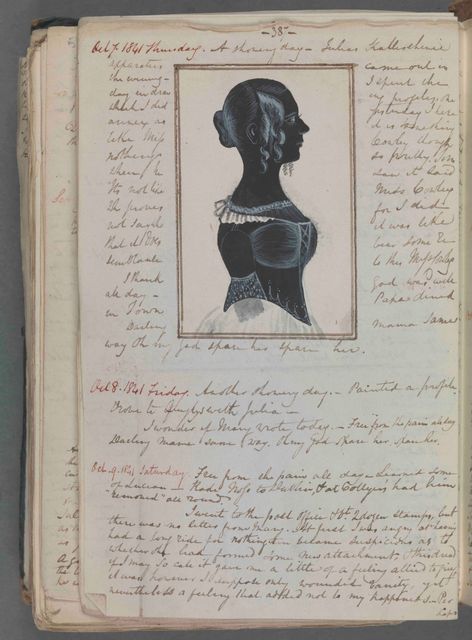

An illustration of Mary in the diary

When she moved away from Dublin to serve as a governess they exchanged letters, many of which James transcribed into his diary. The quarrels continued with each accusing the other of writing too infrequently, or being cold, or loving someone else.

The meetings also continued. Mary might visit her sister in Dublin or she might travel with the family she worked for and slip away to meet James.

Almost inevitably, though, the affair fell apart. James’s family didn’t approve. Mary, although educated, wasn’t the right class. I made some half-hearted attempts to trace Mary but found nothing except for what James said about her.

I didn’t really know what to do with the diary but it lodged in my brain. Years later, I teamed up with historian Ciaran O’Neill and we wrote an article about their love affair. Ciaran’s in-depth knowledge of Irish elites allowed us to flesh out James and his family and his concerns. But Mary was a mystery and we were both a bit dissatisfied.

James provided cryptic hints as to what had happened. A fastidious editor of his own work, he wrote over the diary entries in 1848: “What a fool I was in those days! However, never had man such a triumphant triumph as I had over this ‘angel’ of my first love wh[ich] lasted some 4 years.”

We could only speculate as to what this triumph was. In the article, Ciaran and I place some weight on a scandalous night that James and Mary spent at a hotel in Blessington. This event, and its aftermath, seemed to hint at the whiff of scandal clinging to Mary.

The couple met at the hotel for a meal and each was to travel onwards. Heavy snow encouraged them to stay put. They slept in separate rooms but nonetheless this was highly irregular behaviour and they were both punished for it.

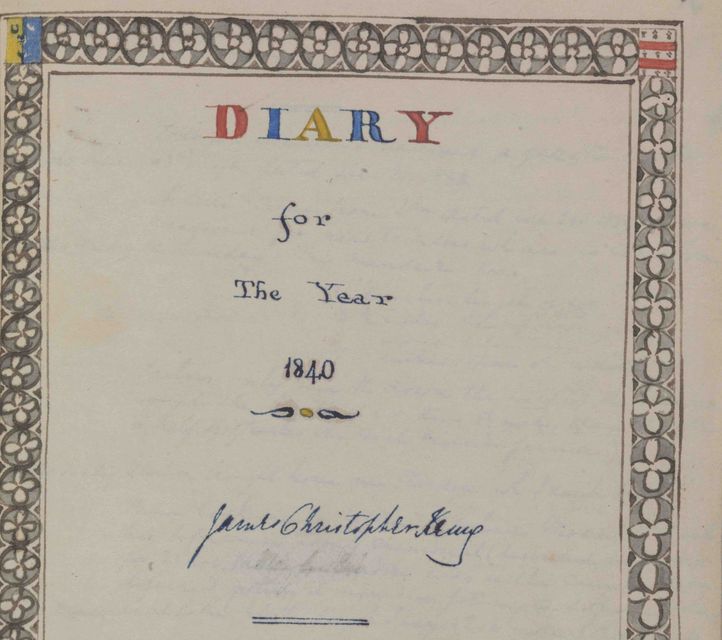

The diary of James Christopher Kenney

James’s father invaded his room, looked through his personal papers and demanded he break off the acquaintance. He accused Mary of sexual impropriety with a number of men. James made the right noises but continued his meetings with Mary for several more years.

Mary’s reputation, possibly already tarnished, was now in tatters with the man she loved. She took extreme measures.

She hired two doctors to examine her and declare that she’d never been pregnant. James wasn’t convinced — he was disgusted. Nonetheless, the affair continued and Ciaran and I could not discover what the final “triumph” was or why James referred to Mary as “an angel”.

Mary has vanished. Perhaps she married (although we could find no record of this in Ireland) or emigrated. We found a promising death certificate but couldn’t be sure it was hers. We will probably never know.

This kind of material is like gold dust in the archives, especially in the 19th century. I have spent weeks of my life reading diaries and letters that consisted mostly of lists of dull engagements, books read, clothing purchased, complaints about the weather, cliched comments on political affairs. People often express love for parents or children or siblings and occasionally for pets but most often for God.

James’s diary overflowed with his longings, sometimes to the point of absurdity. “I told her that she was an icicle pure & bright but cold,” he complained. “I c[oul]d not get her to say what I wanted. She asked me what that was & I said she could easily guess the three words (I LOVE YOU were the words I meant).” Yes, James, we guessed.

But the diary also made me angry. James wrote hundreds of pages about Mary and then, sometime around 1844, he dropped her and she disappeared. In 1870 he trotted off to Mayo where he married an heiress almost 30 years younger than him.

Clogher House in Co Mayo, the home of James Christopher Kenney

Then he died and left her to raise five children. One of his sons, James FitzGerald-Kenney, became Fine Gael justice minister in 1927.

Mary presumably wrote the letters James transcribed in his diary and more besides. She might have even kept a diary herself. So far as we know, these materials have not survived.

Historians are often trying to make up for these absences in the archives, piecing together stories from as many scraps as they can find.

Many 19th-century women, outside a charmed circle of elites, are glimpsed sideways, from the point of view of fathers or husbands or siblings. The poorest women, like the poorest men, are only visible from the point of view of the institutions that came to house them when they were abandoned by any or all of the above.

Was Mary really having sexual relationships with men outside of marriage? Did she get pregnant? Was she in love with James or just a gold-digger? Why was no one looking after her, leaving her to fend for herself in erratic employment and at the mercy of prowling men? She once reported to James that she was assaulted by his uncle.

Ciaran and I could not answer these questions. We’ve done the best we could do in the article. I decided to speculate in the form of fiction. Mary made her way into my novel, The Grateful Water, transformed into one its central characters — Anne.

In the novel, Anne’s circumstances are remarkably similar to Mary’s. She too has a mother who married a dancing master and reduced their family circumstances. Her mother also dies and, when her father remarries, Anne becomes a lady’s companion like Mary.

Bored and lonely, she too is drawn into a risky affair. I filled in her side of the story, made her a person with her own thoughts, desires and motivations.

Front page of James Christopher Kenney’s diary

I am not the first historian driven to speculation and fictionalisation because of frustration with what recorded history has left us. I said historians are nosy but that’s just a flippant way of saying we are deeply curious about human beings. We want to know how people thought and felt in the past because we are always asking ourselves: how different are we really?

History is a way of telling stories about ourselves as much as it is a way of telling stories about the past. I have no problem with history fumbling for understanding rather than being a quest for truth. And in this fumbling, historical fiction has its place.

From Benjamin Black to Nuala O’Connor, Lucy Caldwell to Adrian Duncan, Leeanne O’Donnell to Martina Devlin, historical fiction is thriving in Ireland.

At the heart of this success is our curiosity for the unknown story, the unseen figure, the unheard voice. This can only be good for history and historians too.

‘The Grateful Water’ by Juliana Adelman is published by New Island Books