Fitness

Minimally invasive surgeries for spontaneous hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage (MISICH): a multicenter randomized controlled trial – BMC Medicine

Clinical characteristics

Between July 1, 2016, and June 30, 2022, 1226 ICH patients from 16 hospitals across China were screened for eligibility; 733 patients were randomly allocated to the three study groups. Among the 493 patients who were excluded from the trial, 318 (64.5%) did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 175 (35.5%) refused consent. Further 12 patients were excluded due to ineligible hematoma volume or consent withdrawal before treatment and were not included in the analysis. Finally, 721 patients (239 in the endoscopy group, 246 in the aspiration group, and 236 in the craniotomy group) received treatment and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis (Fig. 1). The demographic and baseline characteristics of patients were summarized in Table 1. The results showed that 497 (68.8%) of 721 patients were men and 225 (31.2%) were women (mean age 56.7 years, SD 11.3); 395 (54.8%) were left-sided hemorrhage and 326 (45.2%) were right-sided hemorrhage. For hemorrhage location, 515 (71.4%) were located mainly in the basal ganglia, 144 (20.0%) located in the lobar region, and 62 (8.6%) located in the thalamus. Forty-eight (20.1%) patients in the endoscopy group, 53 (21.5%) patients in the aspiration group, and 42 (17.8%) patients in the craniotomy group involved intraventricular hemorrhage (P = 0.598). The mean Graeb score of these patients were 2.5 (SD 0.8) in the endoscopy group, 2.7 (SD 1.0) in the aspiration group, and 2.6 (SD 0.9) in the craniotomy group (P = 0.264). On admission, the mean hematoma volume was 49.2 mL (SD 17.7, range 25.0–112.3), and the median GCS score was 9 (IQR 7–11). Medical conditions, past medical history, and the proportion of patients taking anticoagulants were similar among three groups. The preoperative characteristics of patients were balanced and comparable among three groups.

The mean hematoma clearance rate was 88.3% (SD 20.8) in the endoscopy group, 60.3% (SD 25.6) in the aspiration group, and 86.5% (SD 17.9) in the craniotomy group (P = 0.000). The time required for surgery was 1.0 h in the aspiration group, 2.0 h in the endoscopy group, and 3.5 h in the craniotomy group (P = 0.000). In terms of intraoperative blood loss, endoscopy (88 mL) and aspiration (38 mL) was less than that of craniotomy (268 mL) (P = 0.000). The percentage of patients receiving intraoperative blood transfusion was 8.4% (20/239) in the endoscopy group, 2.8% (7/246) in the aspiration group, and 24.6% (58/236) in the craniotomy group, with statistical significance (P = 0.000). Nearly one-third of patients in the craniotomy group (31.9%, 75/236) developed stroke-related pneumonia, which was higher than that in the endoscopy group (22.6%, 54/239) and the aspiration group (18.3%, 45/246), the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.002). The incidence of intracranial infection was 4.6% (11/239) in the endoscopy group, 6.9% (17/246) in the aspiration group, and 5.9% (14/236) in the craniotomy group, with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.553). The median time in NICU was 5 days in the endoscopy group, 4 days in the aspiration group, and 6 days in the craniotomy group (P = 0.042), though the median hospitalization time were similar among three groups (22 vs 23 vs 23, P = 0.083). The mean hospitalization expenses were ¥92,420 in endoscopy group, ¥77,351 in aspiration group, and ¥100,947 in craniotomy group (P = 0.000). Stereotactic aspiration was the most economical surgical method. The general clinical results were summarized in Table 2.

Functional outcome

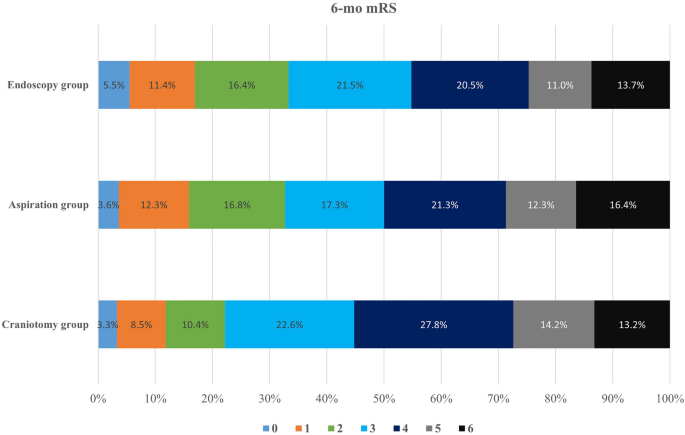

Ten patients in the endoscopy group, 13 patients in the aspiration group, and 14 patients in the craniotomy group crossover to other treatment groups. The reasons for cross-over contained refusal by relatives (18), neurological deterioration (8), relative contradiction for craniotomy or endoscopic surgery due to other major clinical event (6), and reason not recorded (5). The statistical analysis was based on initial grouping. At 6 months after ictus, 70 patients were lost to follow-up. Of the 651 patients with available mRS scores and BI scores at 6-month follow-up, 73 (33.3%) of 219 patients in the endoscopy group, 72 (32.7%) of 220 patients in the aspiration group, and 47 (22.2%) of 212 patients in the craniotomy group achieved a mRS score of 0–2. The long-term prognosis outcome was presented in Table 3. The proportion of patients with favorable outcome in the endoscopy group and the aspiration group was greater than that in the craniotomy group (Fig. 2, P = 0.017). Compared with small-boneflap craniotomy, the prognostic advantage of endoscopic surgery was 11.1% and that of frameless navigated aspiration was 10.5%. The 6-month mortality was 13.7% (30/219) in the endoscopy group, 15.0% (33/220) in the aspiration group, and 16.5% (35/212) in the craniotomy group. The difference was insignificant (P = 0.717). The median Barthel Index of alive patients at 6-month follow-up was 75 (IQR 45–95) in the endoscopy group, 75 (IQR 55–95) in the aspiration group, and 70 (IQR 40–90) in the craniotomy group. Patients in the endoscopy group and the aspiration group got better quality of lives than those in the craniotomy group (P = 0.019).

Age, gender, preoperative GCS score, hematoma location, hematoma volume, surgical method, and intracranial infection were included in the non-conditional logistic regression analysis to identify any variable that correlated with patients’ functional outcome. Young age, better preoperative GCS score, small hematoma volume, lobar hematoma location, endoscopic surgery or stereotactic aspiration, and no intracranial infection were associated with higher odds of favorable outcome (6-month mRS 0–2). The odds ratios for age, preoperative GCS score, hematoma volume, endoscopic surgery, stereotactic aspiration, and intracranial infection were 1.046 (P = 0.000), 0.848 (P = 0.00), 6.159 (P = 0.000), 1.034 (P = 0.000), 0.383 (P = 0.000), 0.453 (P = 0.003), and 6.518 (P = 0.004), respectively (Table S1 in Additional file 2). Further analysis showed that for patients with supratentorial deep hemorrhages (basal ganglia hemorrhages and thalamus hemorrhages), the probability of achieving a favorable outcome was 30.3% (54/178) for endoscopic surgery, 28.4% (50/176) for stereotactic aspiration, and 14.8% (25/169) for craniotomy. The results had a significant statistical difference (P = 0.001). For patients with supratentorial lobar hemorrhages, the probability of achieving a favorable outcome was 46.3% (19/41) for endoscopic surgery, 50.0% (22/44) for stereotactic aspiration, and 51.2% (22/43) for craniotomy. The prognosis of craniotomy surgery was slightly better, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.900). The probability of achieving a favorable outcome was similar between left-sided ICH (30.0%, 88/293) and right-sided ICH (29.6%, 106/358) (P = 0.542). Among the 125 followed-up patients with a GCS score of greater than or equal to 13 before surgery, 54.8% (23/42) in the endoscopic surgery, 53.5% (23/43) in the stereotactic aspiration, and 42.5% (17/40) in the craniotomy achieved a favorable outcome. The difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.477).

Specified safety event (such as severe rebleeding or sudden brain herniation) rates did not reach the predetermined review threshold throughout the trial. In the endoscopy group, 9 of 239 (3.8%) patients experienced rebleeding after surgery, and 6 patients underwent reoperation. Furthermore, one patient received external ventricular drainage because of hydrocephalus after hemorrhage, one patient underwent third ventriculostomy and fistulation of the entrapped temporal horn, and one patient suffered from bleeding at tracheotomy. In the aspiration group, 15 of 246 (6.1%) patients experienced rebleeding after surgery, 4 patients underwent a second-time stereotactic aspiration, and 2 patients underwent craniotomy. Two patients received external ventricular drainage because of hydrocephalus after hemorrhage. In the craniotomy group, 12 of 236 (5.1%) patients experienced rebleeding after surgery, and 7 patients underwent craniotomy again. Three patients received external ventricular drainage because of hydrocephalus. Decompressive craniotomy was performed in only 8 patients (3.4%) in the craniotomy group. The percentage of patients suffering from rebleeding did not reach statistical significance. At the 1-month follow-up, the mortality rates were similar among the three groups (17/239, 7.1% vs 20/246, 8.1% vs 19/236, 8.1%, P = 0.898). Until 6-month follow-up, 11 patients in the endoscopy group, 24 patients in the aspiration group, and 20 patients in the craniotomy group develop hydrocephalus that required shunt surgery. The difference was insignificant (P = 0.052).