World

One of ‘life’s achievers’ – remembering Tommie Gorman

Right to the end, Tommie Gorman had his finger on the pulse of Ireland.

“I think Sinn Féin will have a sobering election,” he wrote in our WhatsApp group on the day of the recent vote, predicting that if they were to hold a seat in Midlands-North-West, the Sinn Féin brand, not the candidates, would see them through. The seat was lost.

Less than three weeks later it is so hard to believe Tommie is no longer with us, writes his friend and fellow journalist Sean O’Rourke.

Yes, we knew he was facing surgery to deal with a recurrence of the cancer that first assailed him 30 years ago. But he had dodged, ducked and weaved his way through it so often before that we saw him as the ultimate survivor.

On 11 June, he wrote in the Irish Daily Mail: “As was always likely to happen, in recent months, some of the sleeping dogs awoke and began barking.”

But he was confident the surgery would get the cancer back under control because his experience with the disease had made him a glass half-full person.

Sadly, it was not to be and now we find ourselves saying farewell and thanks to another towering figure of the RTÉ newsroom, soon after the passing of Charlie Bird and Tommie’s closest friend in journalism, Jim Fahy, who died in 2022. Three of them gone in 30 months.

As with Charlie and Jim, journalism wasn’t a job; it was Tommie’s life, a calling that didn’t end with his 65th birthday.

There was no one better to work a room. We last met when the British Ambassador Paul Johnston hosted a dinner to celebrate Bryan Dobson’s career in RTÉ; Gorman was barely in the door when he had Johnston deep in conversation to one side.

RTÉ’s loss had become The Currency’s gain when his shrewd insights began appearing in the new online platform.

Dredging a mine of statistics recently, he acutely analysed the growth of independents and Sinn Féin, comparing the decline of the Fianna Fáil/Fine Gael combined vote to the diminishing influence of the Catholic Church, and predicting they wouldn’t surpass a combined 50% again.

Heading into St Vincent’s last week, he was hoping to be well enough to join the RTÉ panel in Belfast for next week’s election results programme.

His chronic illness wasn’t so much a hindrance to a full life as an inconvenience to be managed, and drawn upon to improve services and supports for others.

Having accessed advanced treatment for his neuroendocrine tumours in Sweden via an EU scheme, he helped countless Irish people do the same; he successfully campaigned for the development of a centre of excellence at St Vincent’s Hospital.

Anyone who sought his advice found a sympathetic ear on the phone or – if he could manage it – a visit in person, distance no object.

Like many of life’s achievers, Tommie somehow managed to keep going through the pain of his disease, never letting up.

Just days before his passing he attended a book festival in Waterford, chaired a HSE seminar and walked the pier in Dún Laoghaire, met the RTÉ Director General for dinner, stopped his car to give a lift home to a young man in need, in addition to texting, WhatsApping and calling numerous friends.

Empathy and encouragement were Tommie Gorman’s stock-in-trade. He was a mentor to colleagues young and old, and liked nothing more than to see young talent blossom.

Anyone fortunate enough to get a stint in RTÉ’s Belfast office during his tenure inevitably returned to Donnybrook the wiser for it, having picked up some tricks of the trade and been well briefed on the lie of the northern land.

As Europe and Northern Editor, Gorman’s husbandry of scarce resources was the stuff of legend.

He deployed journalistic colleagues, technical crews and scarce facilities to the best possible effect, trading favours all over the place; he was, after all, the son of the cattle dealer who never forgot the ups and downs, the wheeling and dealing, of his father’s and grandfather’s lives.

This worked wonderfully to my advantage during South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994.

At an ANC event for international media, the chance arose to interview Thabo Mbeki, who would later succeed Nelson Mandela as State President.

It was a big opportunity but my only technical support consisted of a small radio recorder. And then I discovered that the Dutch TV crew queueing just ahead of me were based in Brussels.

“Do you know Tommie Gorman,” I asked. It was like pulling a lever and hitting the casino jackpot. Not only did they record the Mbeki interview and part with a precious TV cassette – they were on hand again a few days later to record an interview with President F.W. de Klerk on a long and steep escalator in a northern Johannesburg shopping centre.

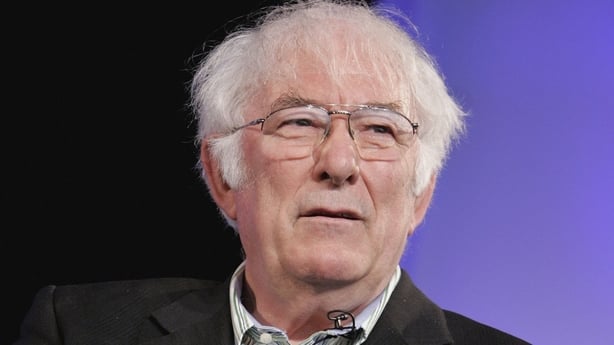

When the occasion justified it, Tommie knew how to take a risk and spend big; $3,000 to hire a helicopter in Athens to track down Seamus Heaney.

Cannily, ruthlessly, he outsmarted the competition for an exclusive interview when Heaney was named Nobel Laureate for Literature.

Re-reading Tommie’s description of the adventure in his memoir brought me out in goosebumps.

That memoir, Never Better, is a brilliantly written story of a reporter’s life in Ireland over the last half century.

It is full of astute insights into Irish, European and British politics as he witnessed them at close quarters.

Above all, though, it is a story of humanity at its frailest and strongest, of opportunities grasped and roots never forgotten.

Tommie’s resourcefulness was surely in his genes. His maternal grandmother was good with the needle, thread and sewing machine, so much so that she could add collars and sleeves to an empty meal bag and transform it into a shirt.

The first time I met Gorman was at the unveiling of a plaque by Knock Shrine PP and airport developer Monsignor James Horan on the wall of the house where then taoiseach Charlie Haughey was born.

It was Autumn 1980 and he was the 23-year-old editor of the Western Journal, in charge of 30 staff.

He had left a journalism course in Rathmines prematurely to take up a reporter’s job with the new paper, offered by his mentor John Healy.

On arrival in Ballina, he discovered the post hadn’t been sanctioned by the Managing Editor Jim McGuire, who instead offered him the inferior role of Sligo correspondent paid by the number of lines published.

“I was in a hole, and I would have to write my way out of it,” Tommie recalled. It did not take him long and soon the staff job was offered.

The venture folded not long after Gorman successfully applied to become RTÉ’s North Western Correspondent.

Tommie’s patch included Derry and he frequently had to drive there at all hours to cover bombings, shootings and other incidents. He worried about the clock only when it concerned a deadline and he was never bothered about overtime.

His move to Brussels was a “temporary” assignment in 1989 when Éamonn Lawlor was called home to be a newscaster but Gorman made it his own territory by dint of graft and guile, persuading Joe Mulholland to leave him there to pursue an array of story ideas beyond the Berlaymont HQ. It surely helped that fellow Sligoman Ray MacSharry had arrived as Agriculture Commissioner.

As with many of his political contacts, Gorman made sure to engage with people in the back office as much as the main figures. He had a talent for building relationships that were both personal and professional. Yes, there were friendships, but business came first.

This was best exemplified by his dealings with Pádraig Flynn, who would have been good for a steer on Commission matters.

That didn’t deter RTÉ’s man in Brussels from using those devastating shots of Flynn refusing to comment as the doors of a lift slammed shut a few days after his infamous comments on The Late Late Show about developer Tom Gilmartin.

I don’t know if Tommie was much of a dancer but he was certainly sure-footed in the bear-pit of Northern Irish politics in the years after the Good Friday Agreement.

Somehow he managed to build contacts, friendships and admirers on all sides. Driven, perhaps, by his experience as a cancer survivor, he dealt with politicians as individuals with weaknesses and challenges, not just people engaged in hardline rough and tumble.

Arlene Foster’s house in Fermanagh was a port of call on his trips home to Sligo, as was Martin McGuinness’s in Derry.

Gerry Adams and Peter Robinson had their family troubles too and Gorman showed understanding of their predicaments while sensitively nudging them in the direction of his microphone.

Sport was one of his passions. However, he managed it, Tommie found time to be John O’Mahony’s video analyst with Leitrim, Galway and Mayo in Gaelic football.

But soccer was his first love, and up to the end he was scheming in the back room of his beloved Sligo Rovers to raise money for upgraded facilities. Watch that space.

And, of course, he revelled in Man United’s glory days in Europe, covering their Champions League exploits and squeezing colleagues into the press box as “technical support”.

A sublime writer, he wrote a beautiful, moving, blog for RTÉ about a Pére Fils trip to Old Trafford with son Joe, who with his sister Moya, and their Mum Ceara, are mourning the loss of a treasured Dad and husband.

To spend time with Tommie either on the phone or in person was to be uplifted, to be cajoled and reassured, and to realise one’s blessings.

After a difficult time late in my own career, he insisted: “You’ve won, Sean. You’ve won. And you have your health.”

He was right, as usual. Rest in peace, my friend.

Sean O’Rourke was an editor and presenter on RTÉ radio and television for three decades up to 2020. He now presents Insights, a series of long-form conversations with public figures for RTÉ Podcasts.