Fitness

Overcoming chemotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer

Researchers have discovered that pancreatic cancer’s resistance to chemotherapy is related to the physical stiffness of the extracellular matrix.

Scientists at Stanford University have discovered that pancreatic cancer’s resistance to chemotherapy is related to the physical stiffness of the tissue surrounding cancerous cells, as well as the chemical composition of the tissue. Their study demonstrates that this resistance can be reversed and discloses targets for new therapeutics.

Dr Sarah Heilshorn, senior author of the paper and professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford, commented: “These results suggest an exciting new direction for future drug development to help overcome chemoresistance, which is a major clinical challenge in pancreatic cancer.”

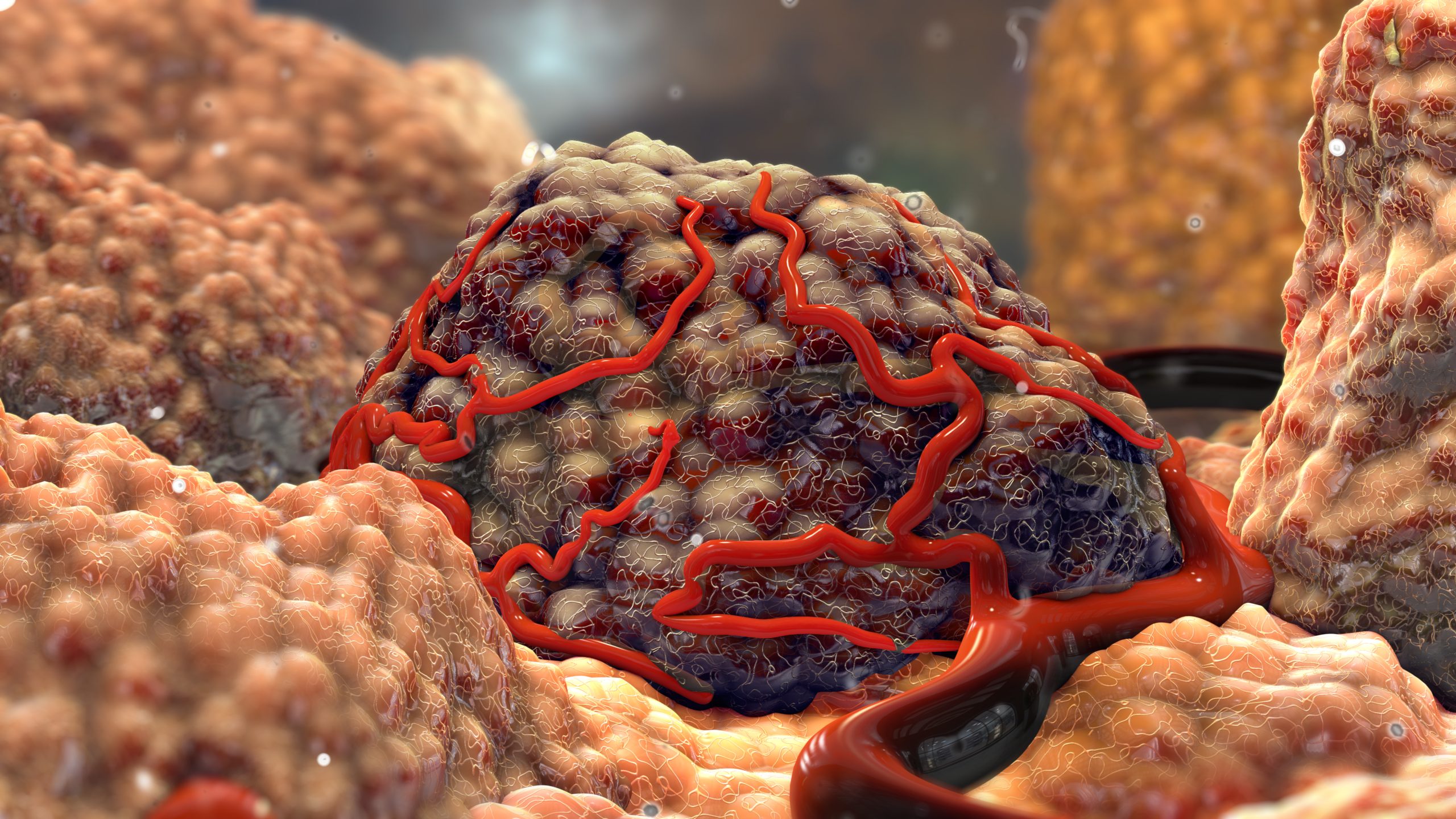

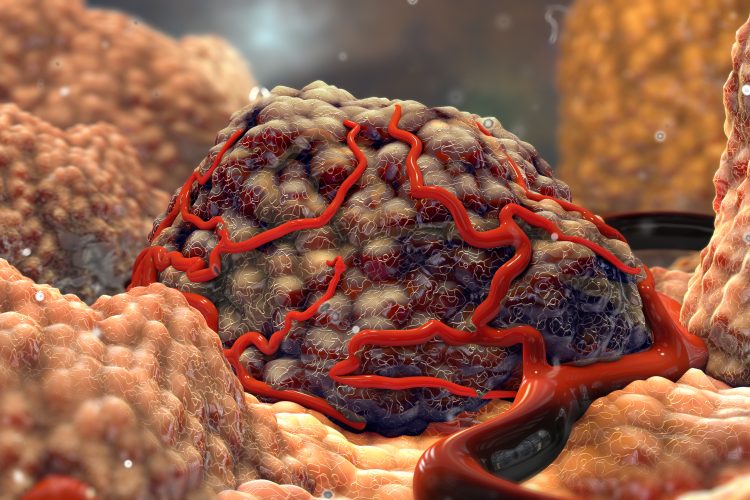

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma accounts for 90 percent of pancreatic cancer cases and was the focus of this research. The extracellular matrix (ECM) becomes notably stiffer in these cancers, which has been suggested to be a physical block that prevents chemotherapy drugs from reaching cancerous cells. However, treatments based on this hypothesis have not been effective in humans.

Alongside PhD student Bauer LeSavage, lead author on the paper, Dr Heilshorn developed a novel method to study these changes to the ECM. The scientists designed three-dimensional (3D) materials that replicated the biochemical and mechanical properties of pancreatic tumours, as well as healthy pancreas tissues. Dr Heilshorn stated: “We created a designer matrix that would allow us to test the idea that these cancerous cells might be responding to the chemical signals and mechanical properties in the matrix around them.”

Receptors in the cancer cells were then selectively activated, and the chemical and physical properties of the designer matrix were adjusted. The researchers discovered that pancreatic cancer needed two things to become resistant to chemotherapy: a physically stiff ECM and elevated amounts of hyaluronic acid, a polymer that helps stiffen the ECM and interacts with cells through CD44.

Primarily, the pancreatic cancer cells in a stiff matrix full of hyaluronic acid responded to chemotherapy. However, after some time in these conditions, the cancerous cells became resistant, generating proteins in the cell membrane that could quickly force the drugs out before they could take effect. This development could be reversed by moving the cells to a softer matrix, even if it were high in hyaluronic acid, or blocking the CD44 receptor, despite a stiff matrix.

“We can revert the cells back to a state where they are sensitive to chemotherapy,” Dr Heilshorn explained. “This suggests that if we can disrupt the stiffness signalling that’s happening through the CD44 receptor, we could make patients’ pancreatic cancer treatable by normal chemotherapy.”

Dr Heilshorn expressed her surprise at the discovery that pancreatic cancer cells interact with the stiff matrix around them through CD44 receptors. Other cancers can be influenced by mechanical properties of the ECM, but these interactions normally work through a different class of receptors named integrins.

The team are continuing to explore the CD44 receptor and the events that follow it is activated in a cancer cell. A greater understanding of the biological mechanisms that result in chemoresistance will enable drug developers to find a way to disrupt the process more easily. Moreover, the team aim to enhance their cell culture model, adding new types of cells to better mimic the environment around a tumour, and altering it to examine other mechanical properties beyond stiffness.

This study was published in Nature Materials.