World

‘Tell them I didn’t kill her’ — last words of innocent Harry Gleeson before he was hanged are recalled as his remains are identified in Mountjoy Prison

Farm manager pardoned by President Michael D Higgins was framed for the killing of unmarried mother-of-seven Moll McCarthy in November 1940

Gleeson was formally pardoned by President Michael D Higgins in 2015, and the family, led by Kevin Gleeson, grandnephew of Harry, have been campaigning for the return of his remains for reburial in his home place, Holy Cross, in Co Tipperary.

Yesterday, the Department of Justice told Mr Gleeson his granduncle’s remains had been positively identified in a burial area within the prison, family sources confirmed. Arrangements for a long-delayed homecoming and family funeral will now be finalised.

On Thursday morning, November 21, 1940, Harry Gleeson was doing the rounds of his uncle’s farm at New Inn in Co Tipperary, making sure no sheep had escaped overnight.

As he approached a remote field, he saw a body on the ground with a little black dog crouched on top of it. The dog began to growl.

A drawing of the gap between two fields where Harry Gleeson first encountered the body of Moll Carthy. Illustration: Fiona Aryan

As Harry had taken dogs with him on his rounds and they were not on leashes, he backtracked to the farmhouse and asked Bridget Caesar, his uncle’s wife, what he should do.

“Go straight over to the garda station immediately and report what you saw,” she told him, and he did.

Barely five months later, Harry Gleeson was hanged in Dublin’s Mountjoy Prison and buried there in an unmarked grave.

He had been convicted of the murder of his neighbour, mother-of seven Mary McCarthy, known locally as Moll Carthy.

A strikingly handsome redhead, she lived in a nearby cottage with six of her children, none of whom had the same father. Her last child had died recently in infancy.

Old IRA members set fire to the thatch on Moll’s cottage. But Moll was a fighter, and she stood her ground

Moll and Harry had much in common. Both were in their 40s and neither had much stake in society. He was working for nothing for his childless uncle John Caesar in the hope of inheriting his farm.

Moll had no job, no husband, just a rundown cottage with a couple of goats and hungry mouths to feed. Harry was a “blow-in” — local people resented the fact that his uncle, who came from Holycross, had outbid them for the farm they thought rightfully belonged to New Inn.

Holycross is barely 15 miles from New Inn, but it could have been on another planet.

That was bad enough, but Moll’s way of making a living to feed her growing brood, which included providing sex for local men, outraged respectable folk. They prevailed on parish priest Fr Edward Murphy to name and condemn her from the pulpit.

When that didn’t send her packing, they persuaded gardaí to seek a court order to have her children taken away because she was neglecting them. In court, Judge Seán Troy sent for the children. After questioning them, he decided they were not being neglected and dismissed the charges.

So when church and state failed to deal with the problem that was Moll, another power was invoked. In republican Tipperary, the IRA was still a strong force. Old IRA members set fire to the thatch on Moll’s cottage. They also burned down a nearby shed, lest she move into that.

But Moll was a fighter, and she stood her ground. She claimed compensation for malicious damages and was awarded £25. Defiantly, she sent her children to Knockgraffon National School where they sat on benches alongside their legitimate half-brothers and sisters.

Moll noticed that when collecting their offspring from school, some mothers were looking very hard at Moll’s children.

“What are ye all lookin’ at?” she demanded. “My kids are every bit as good as yours, haven’t they got the same fathers?”

Harry Gleeson in front of a horse and cart

A kind of uneasy peace prevailed after a local landowner, Anastasia Cooney, made a very public visit to Moll, bringing gifts for her and the children. She was the first “respectable” woman in New Inn to do so.

Anastasia Cooney had driven ambulances in France during World War I and her concern for Moll and her children was a clear message to hostile neighbours — back off. Meanwhile, Moll’s children were growing up and the two eldest were getting work on local farms.

Then, in 1939, Moll became pregnant again. The father, Patrick Byrne, was a neighbour who had also fathered her first son, also Patrick. Byrne’s farm adjoined John Caesar’s, as did that of his in-laws, the O’Gormans. A little girl was born, Moll’s seventh child. The infant was sickly and lived for only a few months.

The world outside New Inn was changing. A long-feared resumption of war between Britain and Germany became reality in 1939. Taoiseach Eamon de Valera, rather than risk provoking the IRA, opted for neutrality.

Many republicans wanted Ireland to take Germany’s side. De Valera, who had come to power with the support of the IRA, needed to keep a close rein on his former allies. In republican heartlands like south Tipperary, neutrality required keeping the IRA activists on side lest they join the war on Hitler’s side.

Sergeant Anthony Daly was posted to New Inn garda station with a brief to watch IRA veterans like Jack ‘The Boss’ Nagle and his sidekick, Thomas Hennessy. Better to know what “the lads” were up to, better too that they knew they were being watched. Sadly for Moll and her children — and for Harry Gleeson — “the lads” had unfinished business.

The presence of Moll and her fatherless brood was a continuing affront to local moral sensibilities. Sergeant Daly visited Moll’s cottage on the afternoon of Wednesday, November 20.

Later that evening, Moll put on what little bits of finery she had and made her way to a disused farmhouse nearby — Lynch’s farmhouse, to meet a man, she thought. She met four: Nagle, Hennessy, Byrne and his brother-in-law ‘Pak’ O’Gorman. In that farmhouse, a shot from O’Gorman’s gun killed her.

Her body was dumped on Caesar’s land, where Gleeson would find it the following morning, her little black dog crouched on her chest.

When Harry Gleeson ran in the door of New Inn garda station the following day to report his dreadful find, Daly already knew Moll was dead. “That morning we knew,” he admitted, many years later in a drunken session in the Reynard public house in New Inn.

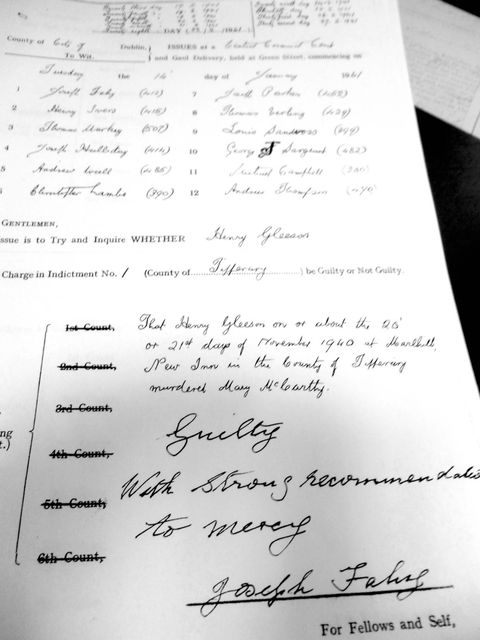

Part of the guilty verdict document signed by the foreman of the jury Joseph Fahy, showing the strong recommendation to mercy. Courtesy National Archives

Garda perjury and a hostile judge duly delivered a conviction, and less than six months later, Harry Gleeson was hanged, on April 23, 1941 — despite the jury’s strong recommendation for mercy.

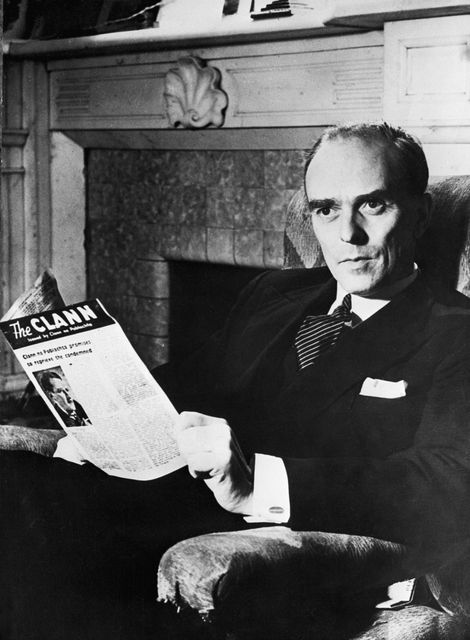

The news that the government had rejected the 7,000-signature petition pleading that Harry Gleeson be saved from the gallows brought lawyer Seán MacBride’s involvement in the case to an end, or so he thought.

Then the day before Harry was hanged, a message came from Mountjoy Prison.

The condemned man wanted to speak to him one last time. MacBride went to the prison. Was he about to hear a deathbed confession?

Nothing of the sort. MacBride found Harry Gleeson calm and reflective. Since they first met barely four months previously, an unexpected bond had developed between the sophisticated lawyer with his fancy French accent and the plain-spoken hurling-mad farm worker.

The finger of suspicion had been pointed at Gleeson, a “blow-in” from another part of Co Tipperary, and he was quickly, far too quickly, many felt, tried, convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. Now he was about to die.

The two men briefly discussed practical matters, Gleeson’s property — he had very little — and other details.

Gleeson told MacBride not to worry about him, he was prepared for death, better prepared than most because he knew it was coming and he had made his peace with God.

MacBride got up to leave. Gleeson also stood up and said: “The last thing I want to say is that I will pray tomorrow that whoever did it will be discovered, and that the whole thing will be like an open book. I rely on you then to clear my name. I have no confession to make, only that I didn’t do it.”

Back in his car, MacBride took out his fountain pen, and wrote down Gleeson’s last instructions to him. That was Tuesday, April 22, 1941. Gleeson was hanged the next day and buried in an unmarked grave in Mountjoy Prison. Seán MacBride died in 1988.

An unexpected bond had developed between MacBride the sophisticated lawyer with his fancy French accent, and the plain-spoken hurling-mad Tipperary farm worker.

On April 1, 2015, Justice Minister Frances Fitzgerald announced an official pardon for Harry Gleeson.

In the intervening years, the torch of Gleeson’s innocence passed on to a faithful few supporters. In 1990, Bill O’Connor, a friend of Harry, published privately The Farcical Trial of Harry Gleeson and it circulated around south Tipperary. Although amateurishly written, it highlighted glaring faults in the prosecution case against Gleeson.

A more considered work — Murder at Marlhill — by barrister and historian Marcus Bourke, was published in 1993.

It seemed Gleeson’s innocence would finally be established. Bridget Caesar, wife of Harry’s uncle John Caesar, enlisted Noel Davern, a local Fianna Fáil TD, to the cause. For a while they appeared to be making progress , but completion of that task would fall to another generation.

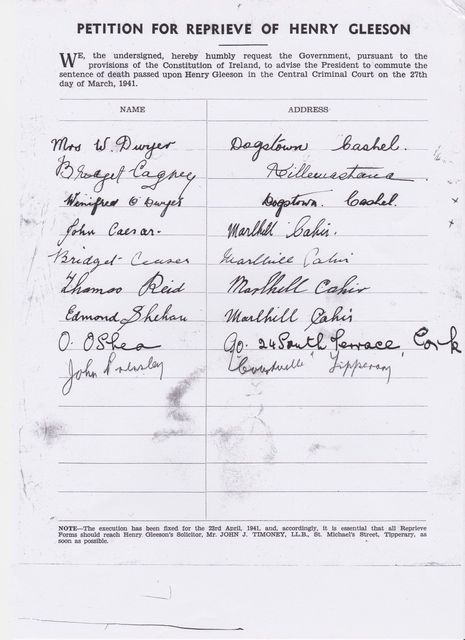

A petition to save Harry Gleeson signed by his uncle John Caesar

Meanwhile, Marcus Bourke, who remained unhappy that his book had not brought about a pardon for Gleeson, had signed a note identifying ‘Pak’ O’Gorman as the man who fired the fatal shot. Bourke had not named the four men responsible for the murder in his book.

The accusation note lay unnoticed in the trial file held in the National Archives until I found it in 2012 when researching my book, The Framing of Harry Gleeson. Bourke told me he was going to name the murderers when writing Murder at Marlhill, but yielded to local pressure to remove them.

In 2012, Harry’s nephew Tom Gleeson and his son Kevin, solicitor Emma Timoney — grand-daughter of Joseph Timoney, a solicitor who defended Harry — and others got together under the chairmanship of Seán Delaney from Borrisoleigh, a Gleeson cousin.

Delaney and his wife Mary founded the Justice for Harry Gleeson group. They put together the case for Harry’s innocence with help from the Innocence Project, a group of law students at Griffith College, Dublin.

Their efforts were rewarded in 2015 when President Michael D Higgins formally announced Harry Gleeson’s pardon, the first to be awarded posthumously to one hanged for murder.

Kieran Fagan is the author of ‘The Framing of Harry Gleeson’