Golf

The GOLF Magazine Interview: Hale Irwin on grit, golf’s evolution and U.S. Open triumphs

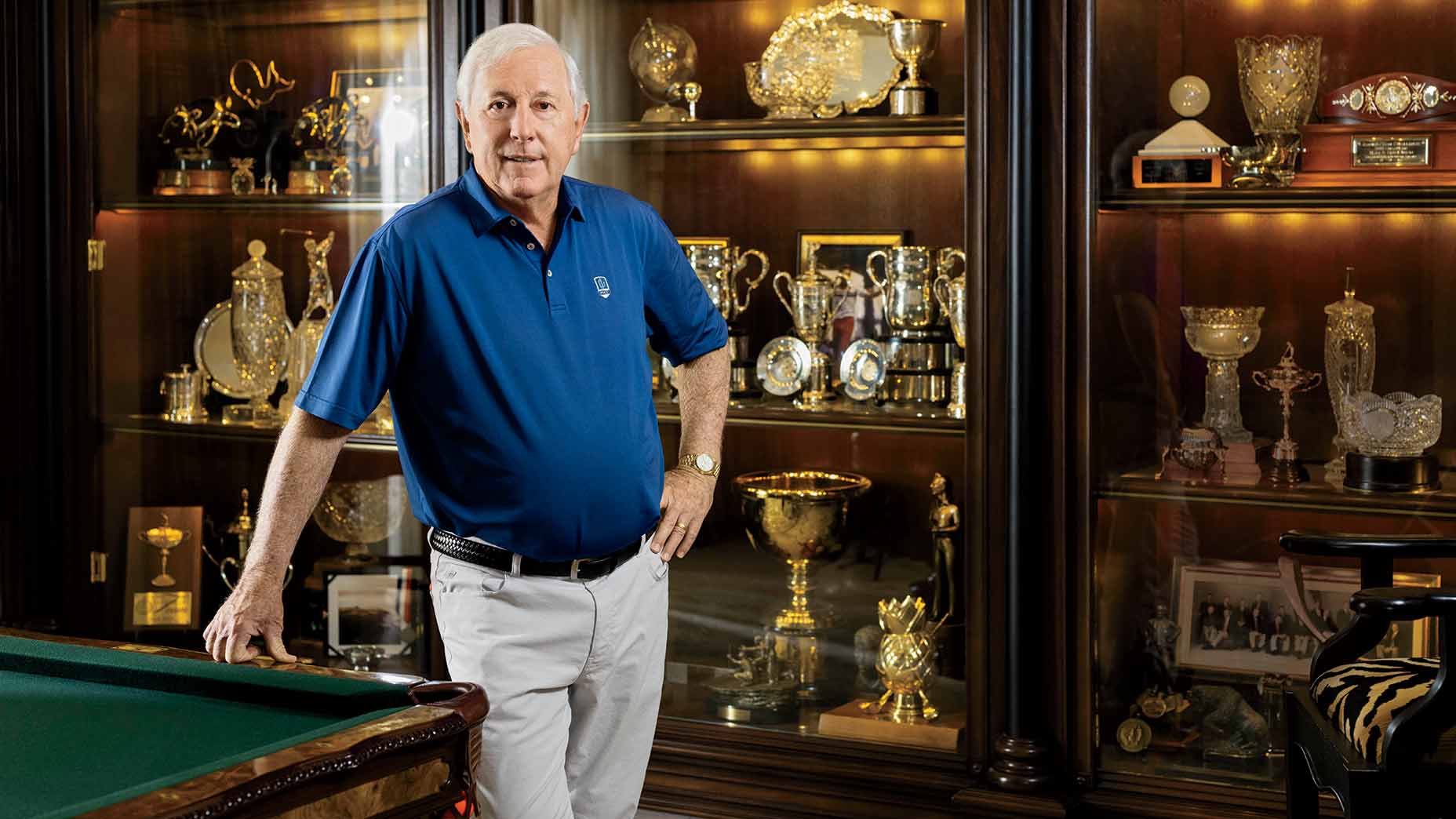

Hale Irwin, pictured in his Scottsdale home, relishing a Hall of Fame life.

Mark Peterman

Hale Irwin lives in the desert outside Scottsdale, in a sprawling, low-slung, cream-colored home, a wing of which is given over to the spoils of his Hall of Fame career. Scores of silver trophies gleam in glass display cases. Triumphal images crowd the walls. In one corner of a sun-lit room, beneath an inscribed photo of Irwin with his friend and pro-am partner, George W. Bush, stand three large golf bags, each emblazoned with the words Ryder Cup, an event that Irwin starred in on five occasions. But the equipment in those bags are the clubs he used in the championship that most shaped his reputation, the U.S. Open, which he won three times.

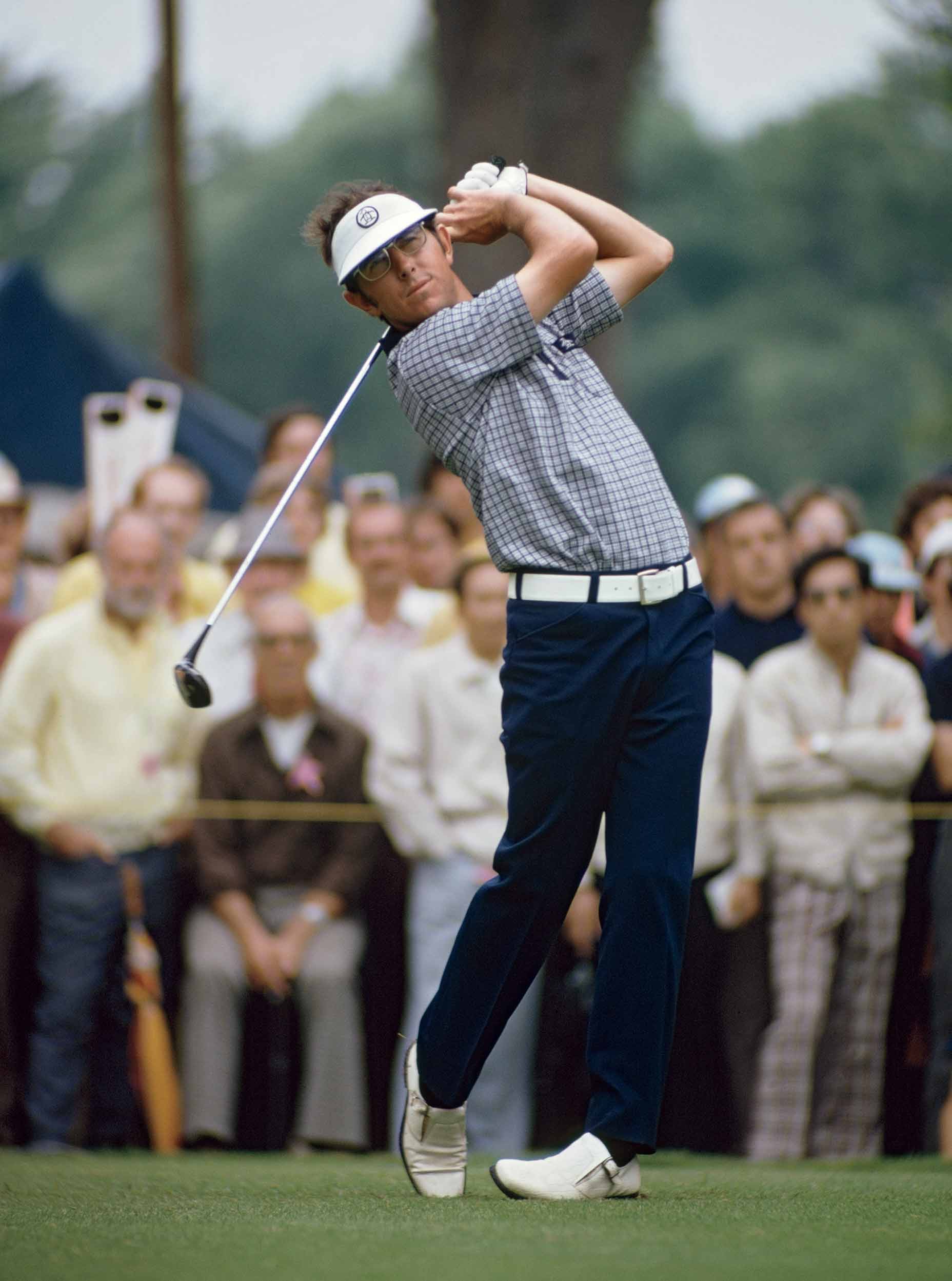

The last of those titles came in 1990, when Irwin was 45, making him the oldest-ever winner of the tournament, a mark that still stands. But the first of those wins remains the best known. Irwin claimed it 50 years ago this month, in the suburbs of New York, on a course with slender fairways, sloping, rock-firm greens and rough longer than Cam Smith’s mullet — a sadistic setup that doubled as the backdrop for what became known as the “Massacre at Winged Foot.” After four torturous rounds in that 1974 U.S. Open, a then-29-year-old Irwin staggered off the 18th green on Sunday, having outlasted the likes of Tom Watson, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Gary Player. His winning score of seven over seems more impressive in retrospect, given not just the brutal course conditions but also the sticks that he was wielding, which today look like primitive gardening tools.

“See how slick this grip is,” Irwin said one recent morning, pulling out the driver he played that week at Winged Foot, a wooden-headed MacGregor Eye-o-Matic with a sweet spot the size of a penny. He turned the club over in his hands, then added, “They don’t make them like these anymore.”

They don’t make them much like Irwin these days, either. On the cusp of his 79th birthday, his dark hair turned silver, the speed well down in his upright swing, Irwin is not the last of his generation. But he is a prototype from the bygone era of a pre-entourage, pre-coddled PGA Tour. With the possible exception of Lee Trevino, no living legend of his vintage better embodies the gritty ethos of a time when the game was filled with bootstrapping, self-taught stars who flew commercial and spent their spring breaks digging answers from the dirt with non-titanium clubs, not sunbathing with their peers.

Even among the scrappiest of his rivals, Irwin stood out for his fire and focus, a competitiveness that was baked in early. Growing up in Kansas, the elder of two sons born to a homemaker and a traveling salesmen, Irwin excelled at multiple sports before enrolling at the University of Colorado. He shined on the golf team. But a football scholarship paid his way.

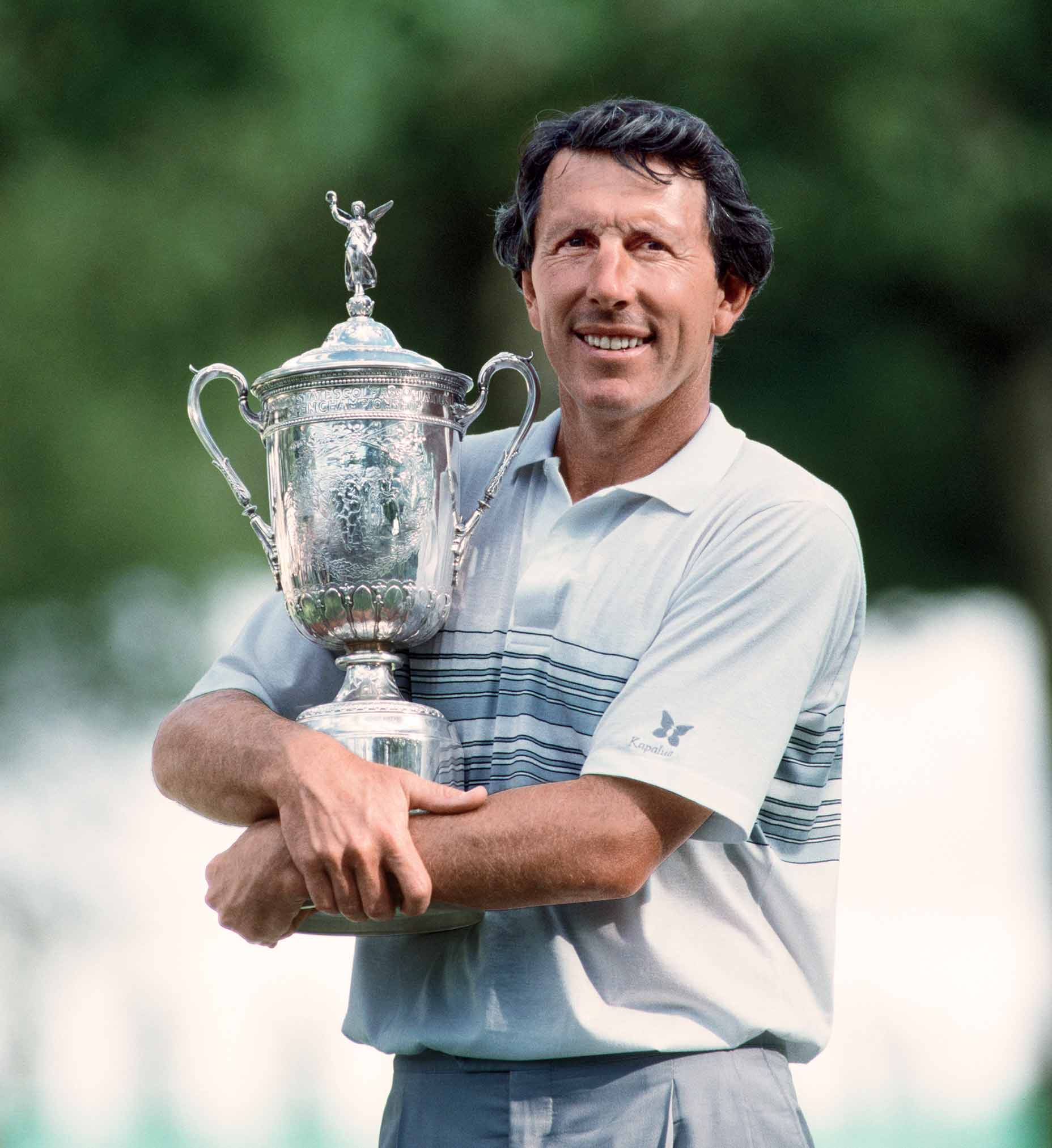

A two-time All-Big Ten defensive back, Irwin brought a hard-nose, gridiron approach to golf. Tough courses suited him, as did the head-on intensity of match play. (Irwin’s career Ryder Cup record was 13-5-2.) Aging did little to dull his edge. His celebratory lap around the 18th green at Medinah, in 1990, where he high-fived fans and blew kisses to the crowd after dropping a bomb that secured his place in a Monday playoff, presaged a remarkable run of dominance — 45 victories — on the Champions Tour that Irwin kept up well into his 60s. “The name is Irwin, not Irlose,” he likes to say.

His tournament years finally behind him, Irwin now occupies himself with varied business interests and enjoys the fruits of family with his wife, Sally, their two children and two grandkids. Though he doesn’t peg it often, he still takes part in occasional clinics and corporate outings while staying in touch with the trends of the game, not all of which he is equally fond. He isn’t one to hold back on his views.

“It probably doesn’t take long to notice that I am something of a traditionalist,” he says.

A half century removed from his historic win at Winged Foot, GOLF sat with Irwin at his house to discuss U.S. Opens past and present, how he feels about the game’s drift from then to now and what he thinks modern pros would shoot if subjected to a Massacre-like test today.

GOLF: It’s been 50 years since Winged Foot. Does it seem that long ago to you?

IRWIN: In some ways, it seems like yesterday. But, at the same time, the game has changed so much. I was just at Augusta for the Masters, and the guys are taking 3-wood off the 1st tee so they don’t hit it too far. Are you kidding me?

You don’t count that as progress?

It’s just so different. The sad part of it, to me, is that we’re losing the connection to the past and the comparison of the greats across generations, from the Nelsons and the Sarazens and the Sneads to Nicklaus and Palmer to Tiger Woods and now Rory and Scottie Scheffler. How do you say who is best?

But isn’t that true of a lot of sports? And isn’t that part of the fun of being a fan? You get to have those debates, and no one can really prove that the other side is wrong.

I guess it depends which pub you walk into. It also depends on the sport. In tennis, sure, you could say the equipment has changed. But has the ball changed in football? Has it changed in basketball? Golf is one of those more interesting cases where you have to ask, did the technology create the player or the other way around? My take is that technology probably preceded the player, because coaches saw that you didn’t have to be as precise and you could go for the long ball.

On that note, how do you think today’s players would fare on the Winged Foot setup you faced in 1974?

Oh, they’d beat seven over.

Is that at all because they’re better athletes and better golfers? Or is it purely because of the equipment?

They’re not better athletes. They’re in better shape. And with the clubs today, they hit it so far. I saw one of the new-model drivers recently — it looked like a truck tire. The one thing I favor from my era is I like to see shots that you had to manipulate. That’s the way I played. I hit it as low as I could and high as I needed to. Today, you just hit it. And if you’re debating between an 8-iron and a 9-iron, you just hit the 9 or maybe even a wedge.

Popperfoto via Getty Images

In 2020, Bryson DeChambeau won at Winged Foot with a bomb and gouge approach. Did it bother you to see the course cut down to size like that?

I watched that on television and I didn’t remember some of the holes I saw. They’d widened some greens and made the entry into a number of them wider. A lot of the trees had been trimmed back instead of hanging down so low you had to duck under them. Not to say it was an easy golf course. But it was easier to play than it was in 1974. I know because I went out and played it after [the 2020 U.S. Open].

The rough was plenty deep when DeChambeau won, though.

I’m not saying he wasn’t impressive. You can’t say a 350-yard drive is not impressive. But you can say it is very different. When you talk about a hole like the 17th, where they’re taking it over the trees on the drive, we couldn’t have sniffed that in our day.

Which then leaves a wedge in.

In 1974, a wedge was my third shot on a par 5. What I can tell you for certain is I have never seen rough like I saw that year. It was just so long and tough. Even if the ball nestled on top of it, the grass would still wrap around the hosel. And the greens. When the best player in the world putts off the green on the 1st hole, you know things are getting serious. It was definitely the toughest conditions I ever came across where the weather wasn’t a factor.

At the time, a lot of people thought the USGA had overcompensated in response to Johnny Miller’s famous 63 at Oakmont the year before. Miller himself suggested the Winged Foot setup was almost a kind of payback. Do you think that’s what was going on?

I don’t know. Maybe there was a bit of that. Johnny played a heck of a round. But there’d been rain that week at Oakmont and the greens were very receptive. In part, maybe the USGA didn’t like what had happened. There was probably some turmoil from within. But, as much as anything, I think it was just that Winged Foot presented an opportunity to set up a very rigorous test. It was more, “This course is a bear, and we can make it even more so. Let’s see what we can do.”

You’ve often told the story about all the complaining about the setup you heard from other players — you figured you had them beat before the tournament even began.

The pall was so thick in the locker room after Monday and Tuesday, you could have cut it with a knife. I concluded that 70 percent of the field had checked out.

Was there anything particular someone did or said?

I wish I could remember something specific. It was just a general defeatist attitude. You could sense it. And no wonder. They knew they were about to get their butts handed to them. We all were.

But your attitude seemed more optimistic. Or, at least, determined. Was that something you were born with or was it a mindset you had to develop over time?

I’m sure it was in the DNA. I’ve been around sports my whole life, and I never liked to do anything halfway. Just to dibble and dabble in something seemed like a waste of time to me. But there’s also something my dad always said: “Don’t start something you can’t finish.” That was my mantra. Whatever it is, give it your best shot.

Your dad introduced you to the game. Did he also teach you the finer points of the swing?

Not so much. My dad would take small clubs, cut them off and wrap them with electrical tape and off I’d go. We were in [Mickey] Mantle country, near the Oklahoma line, and baseball was probably the sport I played best. But golf intrigued me. It was something I could do on my own, and I enjoyed that. I didn’t play any tournaments. Our local course was a nine-hole sand-greens course. There wasn’t even a pro. My mom would take me out there with a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich. I’d hit some shots, look for balls and get poison ivy, and then she’d come back and get me for baseball practice.

Popperfoto via Getty Images

But football was what got you through college. Do you think you could have made it in the NFL?

There was a team or two that expressed some interest. At one point, I heard that Vince Lombardi wanted to talk to me. That got my attention, but… I was six-feet tall and 180 pounds, quick over a short distance but slow by any other means. At Colorado, I was getting beat up pretty good. I was playing two-ways, quarterback and defensive back. After my sophomore year, I almost quit the team because I hurt my shoulder. I told my coach, I’m not sure I’m ready for this. But I could also hear my dad’s voice in my ear: “Don’t start something you can’t finish.” The older I get, the more I believe in that philosophy.

Was getting knocked around on the field what convinced you to ultimately go all in on golf?

As a graduating senior, I had to make a decision. I had a degree in marketing. That’s one option. Vietnam was raging. Football had expressed some interest. But 56 years ago this month, I went down to Florida. PGA National. Fifteen spots for over 100 players over eight rounds of Tour qualifying. A big catalyst for my decision to go was probably winning the NCAA [golf] championship my senior year. That showed me that I could compete with my peer group. Could I also compete with Nicklaus and those other guys? One step at a time. Something that helped me immensely was that my successes happened incrementally. I had a chance to learn, which the young guys today don’t often get. It’s just, whoosh, and off they go.

Which you think hurts them.

I do. Some of these kids aren’t ready for the demands of what comes at them when they turn pro. And they’re being taken advantage of with some of these team offers. If a guy plays dead, he’ll still get $2 million. So, of course, someone is going to get their hooks in them, take their 15 or 20 percent, bleed that kid until he can’t go anymore and then move on to the next one. I don’t like it.

I know you didn’t have a regular swing coach. Or a sports psychologist. Or a traveling chef or any of that. But what if you had had access to stats like Strokes Gained in your day? Do you think you would have taken advantage of that kind of data?

No interest. Simply because I know my game. I know the window I’m trying to hit. At Winged Foot, I knew I wanted to be below the hole because I wanted an uphill putt. I didn’t want to be putting downhill out there. I don’t need stats to tell me that.

On Tour, you had a reputation for being pretty intense. There was once even a player poll that named you “least favorite personality” to play with. Were you aware of that reputation? Did it bother you?

[Holding up his iPhone] This will answer your question.

How so?

It’s a note I sent to Scottie Scheffler after the Masters. It says, “Continue to be you and not what others may want you to be.” Does that answer your question? I’ve always been competitive, and I don’t apologize for that. Some people take that wrong, but it was never against them. Was my demeanor intense? Absolutely. That’s how I got through sports. I don’t want to live without intensity. I can’t do that. With intensity comes greater satisfaction.

It definitely seemed to make you a great fit for the U.S. Open. But you had a bunch of top 10s in the Masters, and there was a famous close call at the Open Championship in 1983, where you missed that little putt. Do you ever think about what might have been?

That putt was an error in judgment. It wasn’t anger. I went up to knock it in left-handed and I stuck the putter in the ground. It didn’t look like a stroke. But I knew it was. My approach is just to move on. It doesn’t enter my life much. And if it does, it’s in and out. There’s too many good things in life. Why dwell on the bad?

You also had a good chance in 1984, when the Open returned to Winged Foot.

I was leading going into the last day, playing with Fuzzy [Zoeller]. It was a pro-Fuzzy crowd. But really, I wasn’t playing great. I was fighting it. My dad was dying of prostate cancer, and I was hoping I could make it one more win for him, 10 years since my first time around at Winged Foot. I put a lot of pressure on myself, and I built a mountain I couldn’t climb. But I learned from it.

Chris Condon

When you won the U.S. Open again, in 1990 at Medinah, it seemed to come out of the blue. Did you have any inkling that something good was about to happen?

At that point, I was what you would call a player of past repute. I’d just started my design company. I could still hit shots, but I wasn’t playing great. At the end of 1989, though, I did a little exercise where, on some yellow-lined paper, I wrote down things I remembered from the tournaments I’d won. That got me thinking as a player again. It got me back on to what made me good.

Which was?

I’ve looked for that paper. I wish I still had it. But I’ve always told people that I’ve learned the most from the things I do well, not from things I do badly. If you focus on what you do well, it takes the negativity out of your thinking. For me, that’s my posture, alignment and tempo. If I put those three things together, everything else tends to fall into place. So, when the 1990 season came, I could feel it coming. I was hitting shots. It’s not as if I couldn’t play.

When you drained that long putt on 18 and did your victory lap, did you think you had done enough to win?

Not outright. But I’d achieved my objective. On the 10th tee of that final round, I was one shot out of the top 15. When I birdied the 11th, finishing in the top 10 became my goal. When I birdied 12, top 5 became the goal, and so on. I use that story when I talk to kids because I want them to understand, it’s the same person who was standing on the 11th tee. Always have a goal. But then be prepared to reevaluate it.

Another event you played well in was the Ryder Cup. But you never got the captaincy. Was that a disappointment? Was it a job you ever lobbied for?

For years, you had to have won a PGA Championship, but then that changed. I would have loved to have been a captain. I always wore my country’s colors proudly. But I didn’t want to say, “I’ll be your captain and I’ll be great.” I didn’t want to do that because that’s not me.

We talked earlier about whether Miller’s 63 at Oakmont influenced the setup at Winged Foot. Do you think the setup at Winged Foot did the same for U.S. Opens that came after?

No doubt. But there are a lot of factors involved. There’s nothing wrong with a tough setup. It should be tough. But how do you go about protecting some of these older courses from the modern game? You want it to be tough but not tricked up. You take a course like Merion. There’s only so much you can do. [In 2013] they said the players weren’t going to shoot too low and they didn’t. But I also saw putts that rolled up toward the cup and rolled back. That’s getting into the range of goofy.

Where do you draw the line?

I think you’ve got to get out ahead on the equipment. Some of us have been saying it for years. The USGA and R&A need to get off their you-know-whats and bring the ball back, and not 10 years from now. Take the driver size back from 460cc to 350ccs. Or with the modern driver, let’s see how they do with a balata. At the same time, I think you have to be very careful with the courses you choose.

That seems to be the philosophy behind establishing anchor sites like Pinehurst, this year’s host course. Will you be attending?

Oh, I don’t know. Why would I?

Because you’re Hale Irwin.

Getting there is a lot.

What do you mean? You fly to Raleigh and drive an hour.

Yeah, and they put me up for a couple of nights and then what? A rubber-chicken dinner? Anyway, I don’t travel as easily as I used to.

But you’ll watch it, right?

I’ll tune in. I’m looking forward to seeing the course. I hope they haven’t changed it too much.

***

ALL HALE! His Hall of Fame career at a glance

PGA Tour wins: 20

Major championship wins: 3 (U.S. Open: 1974, 1979, 1990)

PGA Tour cuts made: 525/661

Career PGA Tour earnings: $5,966,031

Champions Tour wins: 45 (2nd most all-time)

U.S. Senior Open wins: 2 (1998, 2000)

PGA Seniors’ Championship wins: 4 (1996, 1997, 1998, 2004)

Champions Tour cuts made: 469/481

Career Champions Tour earnings: $27,158,515

Champions Tour Player of the Year: 1997, 1998, 2002

World Golf Hall of Fame induction: 1992