Tech

The satellites using radar to peer at earth in minute detail

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSynthetic aperture radar (SAR) allows satellites to bounce radar signals off the ground and interpret the echo – and it can even peer through clouds.

Clouds cover around two-thirds of the world at any one time, preventing conventional satellites from seeing much of the planet.

But now a declassified technology known as synthetic aperture radar (SAR) can be installed on satellites to “see” the Earth’s surface in the dark, through the clouds (or the smoke of wildfires), to provide a constant unobscured view of our planet, and show changes on the Earth’s surface in great detail.

Previously used to equip only a relatively small number of large commercial satellites, this technology is now being combined with constellations of inexpensive nanosatellites in low-Earth orbit by start-ups such as Iceye and Capella Space. The goal is to provide round-the-clock observation of nearly anywhere on the planet for everyone from non-governmental organisations, to military customers.

“SAR satellites are capable of a wider coverage and higher-resolution images than their optical rivals, day or night. You don’t have to wait for the clouds to clear, you don’t have to wait for the rain to stop,” says Holly George-Samuels, an associate scientist at security and defence contractors QinetiQ. “If you need the information, you can go and get it now, and it will be superior to an optical image.

“With centimetres resolution you can even see sheep tracks through grass.”

Getty Images

Getty Images“People told us back in early 2018 that it was technologically impossible to make a small version of a SAR satellite,” says Eric Jensen, CEO of the US arm of Finnish start-up Iceye. “It just couldn’t be done, and even if it could be, you were never going to get enough performance out of something the size of an American dishwasher.

“In a pure kind of entrepreneurial way, we said: ‘Thank you very much for your feedback, but we’re going to try it anyway.’ Now we are building satellites 100 times cheaper than 20 years ago and launching them four to five times faster.

“We’re at a tipping point.” SAR is poised to upend the ways we observe our own planet.

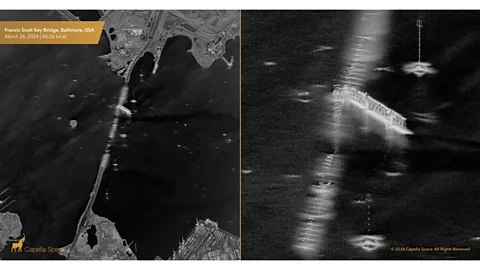

This year, they have been used to quickly reveal the damage caused by the Baltimore Francis Scott Key Bridge incident.

But their potential does not stop there. Nasa Earth scientist and SAR specialist Cathleen Jones uses the satellites “to look at all kinds of hazards”.

Most of California’s water is in the north but most of its population in the south, and the California Aqueduct transports water from one to the other. “If the aqueduct sinks in one location, it reduces the amount of water flows through that point,” says Jones. “So, SAR enables me to look for movement in the Aqueduct down to the centimetre.”

Similarly, she has used the technology to understand the reasons for sink hole formation in coastal areas like New Orleans.

The 2024 hurricane season is set to begin officially on 1 June in the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, with as many as 25 named storms expected. SAR may have an important part to play in the clear-up afterwards.

“We look at all the satellite images and try to detect where there’s an oil spill,” says Jones, “and this is particularly important after a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, where some of the rigs will be destroyed or damaged.”

Jones does this by measuring light reflectivity. Oil will cause a surface to look flatter and darker on the image.

“We can use this technology to detect where the oil is and where it’s going – and do this very quickly,” Jones says. “It’s much more dangerous when a slick moves onshore into a wetlands ecosystem or where people live.”

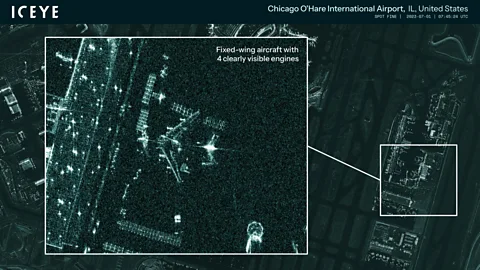

Iceye

IceyeSo how does it work? While optical satellites rely on light from the Sun to illuminate an area of interest on the Earth’s surface, SAR in effect creates its own “sunlight” by transmitting powerful microwave signals from the satellite down to the ground – and which, aren’t affected by weather conditions.

By precisely analysing the signals bounced back, a highly detailed radar image of the area is produced. Frequent passes over the same area means that SAR is particularly good at identifying change on the ground down to the size of a fingernail. But these images look very different from those we see on Google Earth.

“It is more difficult to make sense of SAR images than an optical image, as what you have is a high-resolution ground map of the reflectivity of the scene rather than a photographic image,” says George-Samuels. “So, it is difficult to interpret, and analysts have to be trained up to understand what they are saying. But AI can be trained to interpret images for us.

But the technology is really about collecting data, rather than images. “No one really wants the SAR image: they want to look at the data,” she says. “I was speaking to an ocean scientist who is modelling ocean currents, and they are using the data product of SAR to show the change in height of the sea surface.”

Much of the interest around SAR dates back to a patent awarded in 1954. The now declassified Project Quill satellite launched by the United States 10 years later in 1964 is believed to be the first equipped with the revolutionary technology.

Yet, it is only now – nearly 60 years later – that synthetic aperture radar is making the headlines the technology deserves.

Seventy years from the first patent, the falling price of components have spurred this latest stage in its development. “First – and crucially – is the ability to miniaturise components to build small, cheap satellites and to build them quickly to reduce the cost,” says Beau Legeer, director of imagery and remote sensing at software company Esri. “Then there is the ability to launch these satellites easier, cheaper, and faster than ever before, the availability of venture capital to fund these start-ups, and the early success of SAR in this wider role.

Capella Space

Capella Space“One of the superpowers of SAR is that it not affected by things that affect optical imagery, like different sun angles and shadows, which make it a very consistent data source, which also makes it very good for artificial intelligence machine-learning applications.”

For Eric Jensen of Iceye, the change in attitude of the US government is fundamental for kickstarting the use of SAR. “In the US, the technology was seen as something that the government needed to keep control of, because in the wrong hands enemy nations could look at every allied military installation day or night in high resolution,” he says. “The technology was then largely left for European nations and Canada to develop commercially… with satellites costing $400m–$500m (£320m-£400m) apiece, taking four years to build, and two years to tune when they were in orbit.

“Instead of throttling the development of this new technology, the US has now said, ‘let’s try to use it, let’s welcome it’. What we’ve seen is the US government’s much more willing to work with allied nations who develop core technologies like this than they ever have been in the past.”

Cathleen Jones agrees that “the big, big reason” why SAR is coming to the fore right now is the improvement of technology. “But there is a second big factor as well, and that is this data used to cost a lot of money, and then the European Space Agency and Nasa made their data free to use, and then oh, wow, people started using it.”

Similarly, “all the data will be free to use” from the state-of-the-art joint Nasa-Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) Nisar satellite that is about to launch.

Others have a different view. “I am not sure if revolution is the right word, to be honest,” says Bleddyn Bowen, author of Original Sin: Power, Technology and War in Outer Space. “It’s been around in the military and intelligence communities for a long time, and its only in the news more now because there’s a few commercial providers, and the data is now more available to the government and private industry than in the past.”

Iceye

IceyeNevertheless, the future of SAR may depend on solving the tricky engineering conundrum of increasing the size of the satellite, particularly the antennae and the solar panels used to power it, but at the same time keeping them as small possible so they’re easier to launch. “A big antenna is extremely helpful,” says Frank Backes, CEO at Capella Space, “to increase the fidelity of the image. It’s an interesting physics problem.”

It will also depend on the development of orbital communication networks such as Amazon’s Kuiper, which other spacecraft in low Earth orbit can plug into as well. “This will enable us to transmit our data direct to the user,” Backes says, “and reduce the time it will take from an hour or two to less than 15 minutes. And the nice part is these networks are going up right now.”

But the use of artificial intelligence is fundamental to its future. “AI will excel at extracting the useful information as a data product and presenting that to a person,” says George-Samuels.

In the end, its supporters say SAR will directly impact society simply by the smoother running of supply chains, the more predictable yields of agriculture, or – more importantly perhaps – being kept out of harm’s way during floods or wildfires.

George-Samuels believes SAR will deliver more effective environmental monitoring. “With more information we can act quicker,” she says. “It’s going to save lives.”

Others are thinking even bigger, “It will mean transparency on a planetary scale,” says Backes. “So, in a conflict situation, having information readily available to the general public about what’s going on will eliminate the fog of war, and we have already seen that in the Russian–Ukrainian conflict.”

But not everyone is on board. Some are worried about the dangers of the technology. Its potential to intrude on individual privacy, its use for corporate espionage, and even if it could be used to plan terrorist attacks.

Is hype also a factor? “Private imaging companies always want to create the impression that we will have transparency,” says Bowen. “We will be able to see anything that happens, and will get a warning of anything that is about to happen. But we are never going to have full transparency and full information because the images aren’t the equivalent of live video, and they don’t tell you everything that you may need to know.”

In January 2022, everybody could see that the Russians were massing on the Ukraine border, but nobody could see inside Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s head to know if there was going to be a war or not. “We also never got any imagery or information about anything that was going on the Ukrainian side. There was complete shutter control by the United States.”