Travel

This Lo-Fi Time-Travel Epic May Be the Most Challenging Hard Sci-Fi Movie Ever Made

The Big Picture

-

Hard to Be a God

delves into a chaotic society mired in filth and violence, challenging the notion of stagnation versus progress. - The film follows protagonist Don Rumata in a difficult position, torn between intervening to save lives and preserving a repressive status quo.

- Director Aleksei German’s unique style combines idiosyncratic camera work with immersive filth-filled visuals, posing philosophical questions.

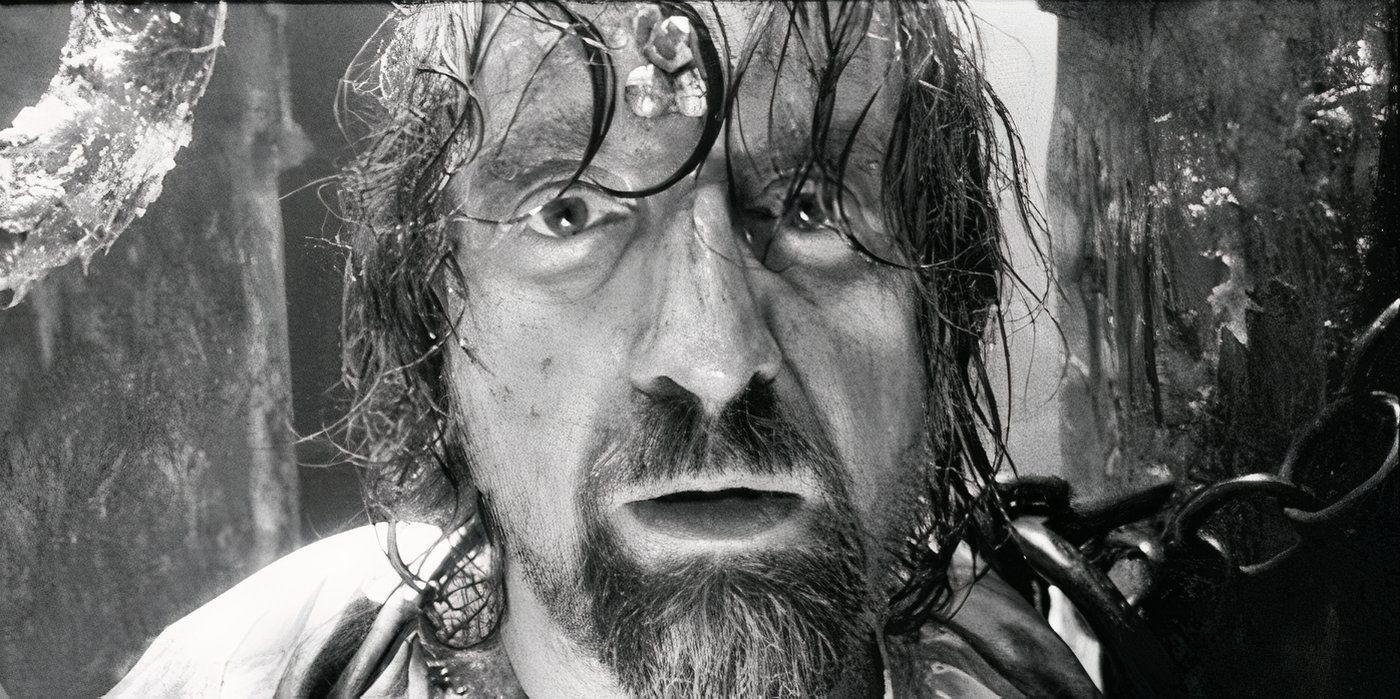

Do you like challenging science fiction? Do you like mud, as well as substances that are similar to mud? If so, consider Aleksei German’s late-career epic, Hard to Be a God. Based on the 1964 novel of the same name by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, the film is set in the city of Arkanar, on a distant planet populated by a species identical to humans, but in an earlier stage of social development. Specifically, Arkanar is stuck in the Middle Ages, and its Age of Enlightenment is permanently delayed by a ruling authority that persists in murdering anyone in the city who attempts to educate themselves. The film is lodged entirely in the perspective of Anton (Leonid Yarmolnik), a visitor from Earth who is disguised as a local lord named Don Rumata, and, because of his superior knowledge, is believed by most locals to be a god. Rumata is code-bound not to interfere too directly in the affairs of Arkanar, and so can do nothing but observe this society that is mired in squalor, inequality, and violence. Though the first half of this three-hour film feels like it plunges you into the chaotic world without much guidance, a plot emerges steadily. By the time the film is over, you have had a strange but riveting experience, one that some would argue is perfect from start to finish.

What Is ‘Hard to Be a God’ About?

At first, Hard to Be a God seems to be about nothing but a series of chaotic experiences. We get a brief upfront bit of voiceover explaining that 30 scientists from our advanced society of Earth were sent to Arkanar, on a less-advanced planet that was expected to be entering its “Renaissance” period of intellectual growth. However, what has developed instead is a violent suppression of intellectuals, artists, and even talented craftspeople – whom the characters in the film derisively call “Wise Guys.” The sense we get of this world early on is one where nearly everyone lives in some degree of filth and disease, and no one knows that life can get any better than this. The film has frequently been compared to the nightmarish paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, but it can also be compared pretty meaningfully to Mike Judge’sIdiocracy, which also uses the idea of socially engineered planet-wide idiocy as a science fiction concept.

When we meet Don Rumata in Hard to Be a God, our single protagonist, he has been living on Arkanar for twenty years. He’s witnessed the execution and murder of countless Wise Guys. He is under orders to protect these people as best as he can, by smuggling them to neighboring cities where the persecution is less acute. But otherwise, he cannot intervene, and is especially forbidden from killing. This is a concept familiar to most sci-fi fans: in the Star Trek universe, the Enterprise explored the galaxy but was prevented from altering events on less advanced planets by the Prime Directive. However, the Strugatskys’ novel, published in 1964, preceded the premiere of Star Trek: The Original Series.

Rumata, meanwhile, has embraced the chaos and degradation of his adapted home. He lives in a castle in the role of a feudal lord, and has a household of many slaves. He drinks throughout the day, has taken a lover from among the local population, and plays long, sad jazz solos on his alien trumpet. He tries to protect those citizens of Arkanar that Earth deems educated enough to advance their society out of the Dark Ages. But he has seen decades of ignorance and death, and has embraced the notion that life is cheap.

‘Hard to Be a God’ Places Its Protagonist in a Difficult Position

Though Rumata has adapted to the status quo in Arkanar, things can always get worse. When Rumata travels to the city to rescue Budakh (Yevgeni Gerchakov), a doctor whom he enjoys talking to, from prison, he learns that the Grays, the fascist police force in charge of executing Wise Guys, have an aggressive new leader named Don Reba (Aleksandr Chutko). Reba is a zealous believer in the local superstitions, and soon he has instigated a military coup, deposing the king of Arkanar and placing the Grays in charge.

Violence ensues. The chaos of the coup places even Rumata’s fellow earthlings in danger. Soon, he is being asked to intervene by his former slaves, who are aware that he has access to superior Earth technology. Rumata must decide whether to intervene on behalf of the slave revolt, though he fears that even if the revolt is successful, human nature will lead the new regime to be just as repressive as the Grays. By this point, surprisingly, we have come to care about many of these characters, enough that we cling to the dim hope that Rumata is willing and able to avert further tragedy, even if it means breaking his vow not to kill.

Who Is Aleksei German, Director of ‘Hard to Be a God’?

Aleksei German was born in 1938 in what was then the Soviet Union. He directed his first solo film in 1971. Most of his films were set during the rule of Joseph Stalin, and were critical of the oppression and cruelty of his regime’s leadership. Though Stalin was dead by the time German was making films, this critical stance made it difficult for him to finance films, and those he did make were often prevented from being released by Soviet censors. German was only able to complete six films over the course of his 50-year career.

Nevertheless, this output was enough to cement his reputation as one of the great directors. Though he never achieved the international recognition of his contemporaries, his work was heralded by cinephiles. Famously, Martin Scorsese attempted to award his fifth film Khrustalyov, My Car! – set during the chaotic aftermath of Stalin’s death – the Palme d’Or when he was president of the jury at Cannes in 1998, but was unable to convince his fellow jury members.

Related

In This Sci-Fi Classic, the Alien Was Jesus All Along

“That power is reserved to the Almighty Spirit.”

Hard to Be a God was German’s final film, and it was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream to adapt the Strugatskys’ novel. The Strugatskys are the most prominent Russian science fiction authors, and Hard to Be a God is one of their best known works. However, German was passed over for the novel’s 1989 adaptation (which featured Werner Herzog in a small role!) for another director. Finally, German was able to get his adaptation made, though production took an unusually long three years. And though it was German’s first film to break through to a larger audience, German was not able to enjoy the recognition, as he died just before the film’s official European release, in 2013.

What Makes ‘Hard to Be a God’ So Unique?

German’s films are not avant-garde or non-narrative, but they do have an idiosyncratic way of presenting information on camera. His style in both of his last two films was to employ long takes on a steadicam, drifting though chaotic events that roamed in and out of frame. Typically, it takes a second watch to get a real handle on the plot of his films, but not more than two. And perhaps not even that if you go in knowing that some extra attention will be required.

Of course, a second watch is a lot to ask for a three-hour black and white film with an unconventional plot. Thankfully, Hard to Be a God is an immersive experience before the plot kicks in. German’s vision of humanity is unlike anything else in cinema. The film, which depicts an alien analogue of the life of a peasant, is famous for its depiction of filth. Though the film is largely set outside, we almost never see the sky; the camera is always angled slightly downward, into the mud and fog. On top of that, German layers a constant stream of bodily fluids. This is largely presented in a humorous way, as it would be in a gross-out comedy – there are a lot of latrines featured, and the characters are constantly blowing snot out of their noses mid-conversation. But German blends in some notes of body horror as well, as life in Arkanar is nasty, brutish, and short.

The truly unique element of Hard to Be a God is also its most mysterious. As the camera weaves in and around the peasants and slaves of Arkanar, they frequently “notice” the camera. Though this leaves the viewer wondering if we are meant to assume that the camera is “present” in the world in some way, either because we’re in the point of view of a character, or of some sort of futuristic sci-fi filming device, there is never any explanation given for this breaking of the fourth wall. It is undeniably effective though, at communicating the artlessness of Arkanar. Its inhabitants are so clueless, they can’t even remember to ignore the camera. It’s a device that doesn’t seem like it should work as well as it does.

Hard to Be a God is not quite like anything else, but there’s plenty to compare it to to give a sense of what it’s like. The most frequent comparison is Andrei Tarkovsky’s historical epic Andrei Rublev. Tarkovsky’s career in the Soviet Union overlapped with German’s, although Tarkovsky received far more acclaim during his life. Though Tarkovsky’s Stalker is also an adaptation of a novel by the Strugatskys, Andrei Rublev‘s god’s-eye depiction of the violent chaos of the life of a medieval serf is more viscerally similar. If three-hour Russian epics aren’t your thing, it’s also interesting to compare German’s gliding camera movements and slightly unsatisfying blocking to the way the camera moves in video games, particularly those that make the best use of the format like Half-Life 2 or The Last of Us. Though Hard to Be a God is unusual and asks more of a viewer than most films, it’s never truly alienating. The logic of its approach, its extreme vision of humanity, and the philosophical questions it poses are all accessible.

Hard to Be a God is available to stream on Kanopy, and to rent on Apple TV+ in the U.S.