Fashion

Who Will Lead Chanel?

The Chanel fall 2024 couture show on June 25.

Photo: Gao Jing/Xinhua/Alamy

Sensing another bottleneck, my driver turned our Mercedes van south at the end of the Pont Royal and then suddenly north, so that we were briefly going the wrong way on a one-way road. “Nice move, Richard,” I said to the driver. He grunted and gunned the van through the intersection before anyone could hit us and then into the tunnel near the Louvre. The Olympics were snarling traffic everywhere in Paris. Many streets and bridges were already closed. And the semi-annual haute couture shows were also going on.

We popped out of the tunnel, and Richard, looking again at his phone, said, “We’ll be at the Opera at ten-oh-four.”

The Chanel show was at the Palais Garnier at 10 a.m. Ordinarily, there’s a grace period for the unpunctual, 20 or 30 minutes. Almost no show starts on time. But as we pulled up to the opera house, at 10:03, I noticed something strange about the situation. The entire area, including the street, was cordoned off by black barricades and patrolled by black-suited Chanel security. There was no else around, no guests.

Oh, shit, I thought. They’re all inside.

I trotted over to the entrance, along with some other laggards, and climbed the steps to the second floor, where everyone was seated along a wide corridor overlooking the grand staircase. People were hardly talking. Usually before a show, you’re up, schmoozing. This felt like church. I took my seat. At 10:10, the show started.

What accounted for this intense focus around Chanel was not the show or the prospect of seeing a collection from creative director Virginie Viard, the former Chanel studio manager and successor to Karl Lagerfeld following his death in 2019. Viard wasn’t a great designer. She had spent her entire career, about 30 years, helping the workrooms interpret Lagerfeld’s sketches — he always drew — and her own collections reflected a certain airlessness that often comes from doing things the same way. In early June, for reasons that are unclear, Viard was fired. Given the apparent abruptness of the decision — which was made by the brand’s president of fashion, Bruno Pavlovsky, and backed by its chairman and co-owner, Alain Wertheimer — there must have been a serious disagreement. Because Viard was suddenly out and the Wertheimers, who have owned the house since the 1950s (and the perfumes for much longer), were not prepared with a replacement, the studio team finished the couture collection. It was classic Chanel prettiness with a dose of opera-inspired capes and glamour and a ravishing wedding dress. Pavlovsky has begun the search for the next designer.

So the real drama at Chanel was happening behind the scenes, in its executive offices in Paris and New York, where Wertheimer lives. And given the intense rivalries in fashion and the amount of media attention and ultimately money that is at stake with such a major hire, you can be sure that executives at LVMH, which owns Dior and Fendi, and Kering, owner of Balenciaga and Gucci, among others, will be watching Chanel closely. “I bet LVMH is racing to get the designers they’ve chosen for jobs to sign their contracts, so they don’t lose them,” an editor said to me with a laugh later that day, before the start of the Giorgio Armani show. For some reason, French fashion brings out the blood sport in people. A headhunter I know in Paris suggested what Chanel should do in choosing its creative director: “The strategy is, How to make Bernard Arnault sick?” Arnault is the chairman and CEO of LVMH and the richest man in France. “You make the choice with this in mind, and you can’t make any mistake.”

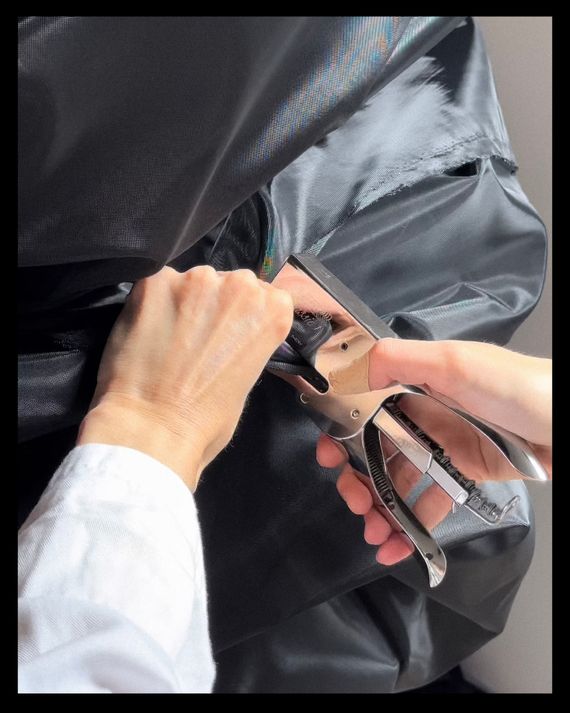

An hour before the Balenciaga show began, assistants whipped up a dress backstage using 47 meters of black nylon gazar and a stapler. “I wanted it to be this ephemeral dress,” said Demna, the designer. Photo: Jacob Ogden.

An hour before the Balenciaga show began, assistants whipped up a dress backstage using 47 meters of black nylon gazar and a stapler. “I wanted it to …

An hour before the Balenciaga show began, assistants whipped up a dress backstage using 47 meters of black nylon gazar and a stapler. “I wanted it to be this ephemeral dress,” said Demna, the designer. Photo: Jacob Ogden.

At the couture shows, you couldn’t go anyplace in town where there were fashion people — the restaurant Voltaire, the terrace at the Costes hotel, the shows themselves — without someone talking about the succession question. And no one seemed interested anymore in the details behind Viard’s exit or whether, in light of her long service, it seemed poorly handled. “Comme ci, comme ça,” a French editor said with a shrug outside the Dior show in the garden of the Musée Rodin.

There’s a good reason people are so invested in this story. Chanel is unquestionably the greatest house in fashion, founded on Coco Chanel’s original straight-line suit, which she proposed at a time when women’s fashion still emphasized boobs, hips, and waists. That line changed everything: Afterward, any look that suggested a feminine, nonathletic body looked out of date. Although Lagerfeld, who was hired in 1983, liked to say that designing Chanel was like decorating a Christmas tree — you just rearranged the signature tweeds, double CCs, and pearls every season — he clearly knew how to change the tempo when necessary. One such moment came in the late ’90s, when LVMH was shaking up the industry by hiring young talent, such as John Galliano at Dior and Marc Jacobs for Louis Vuitton. Chanel had become a bit stodgy, but Lagerfeld, who never liked to be left behind, tarted up the designs. Later, he kept pace with Dior and Vuitton, and at times even surpassed them, by creating monumental fantasy sets — a beach, a spaceship, a huge iceberg — for his shows.

Chanel has not hired a major designer since Lagerfeld: Viard was essentially a custodian of his ideas and methods. It means, then, that this is the most important hire in fashion of the past 40 years.

This is also high stakes because of where the larger industry is. Indeed, for many people, fashion is in a malaise, with too much sameness on the runways. Partly that’s because managers are watching bottom lines and don’t want creatives to take risks, and partly because the number of designers who try to do something surprising and interesting each season is relatively small. Across the industry, many brands just seem muddled, such as Gucci and Saint Laurent, which rely too much on archive designs. Givenchy has been without a creative director for months. I heard from two sources in Paris that Martina Tiefenthaler, who was Demna’s assistant for years, was asked to do a presentation for the Givenchy job. There have also been reports — more like rumors — that LVMH wants Sarah Burton, who led Alexander McQueen for many years, for that job. “They have met the entire world,” the Paris headhunter said. “They need someone with a new vision who’s going to break everything. I think they’re afraid of anyone a little too edgy.”

There were bright spots at the shows. At Balenciaga, Demna used novel fabrics and methods of cutting. One elegant white column dress was made of melted plastic bags that had been molded on the body for a new material that resembled rice paper. A coat was an embroidery of synthetic human hair, dyed electric blue, though to look at the choppy, silky texture, you’d never guess it was hair. And Daniel Roseberry of Schiaparelli pushed himself harder this season with a superb collection that evoked erotic fantasies, by way of both restrained tailoring and nearly naked dresses built on corsets. But this kind of experimenting and commitment to leaving your audience a little stunned seems increasingly rare.

That’s what frustrates designers and consumers alike. They want new ideas — not merely more decoration but new silhouettes and new ways of experiencing clothes. “People are so hungry for something that is unique to a house,” Thom Browne said. We were standing at the cocktail party before Dries Van Noten’s final show, a career symbolic of an original vision — like Browne’s own, with its redrawing and minimizing of the classic masculine silhouette. For his couture show a few days later, Browne would inventively use muslin — the off-white cotton typically reserved for making prototypes of garments — for his entire collection. He added, “People don’t want what everyone else is doing. And that unfortunately is what too much of the business is looking at. They’re opening up the spreadsheets and they’re saying, ‘We sold this and we want more of that.’ ” Browne shook his head. “That’s not how creativity works.”

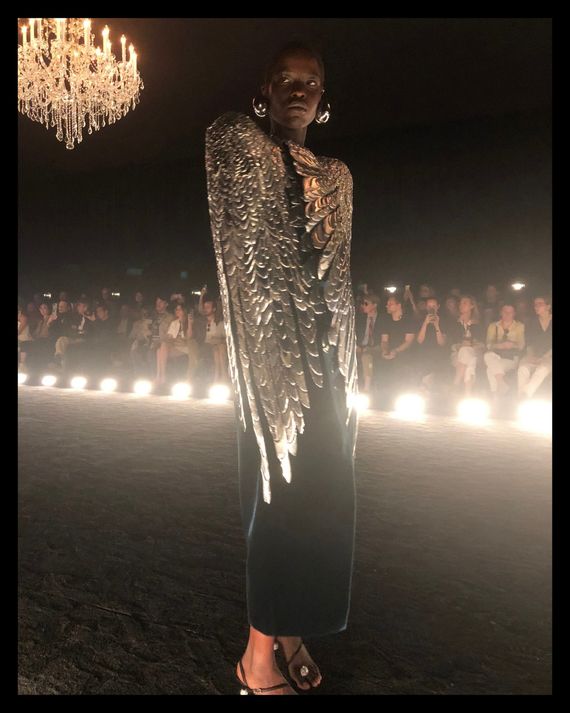

The Schiaparelli show began with an austere cape in black velvet with embroidered feathers made of tin and galvanized in gold. Designer Daniel Roseberry’s collection was a step forward from his earlier Surrealism: The feeling now was erotic, and the models let you know by making eye contact with the audience.

Photo: Cathy Horn/New York Magazine

Under Viard’s creative direction, Chanel lagged in imagination and surprise, even as it prospered. Last year, Chanel reported sales of $19.7 billion. In the high-fashion business, only Louis Vuitton is bigger. That’s not really a contradiction but an indication of how magical the Chanel name is. Given that power — and given how many young people were mesmerized by the artistry of Galliano’s couture show in January and wanted to soak up every detail, from the dresses to the makeup — it’s not hard to see how a great new designer at Chanel can charge the rest of the industry. “It’s a major, major turning point,” a senior LVMH executive said of the change at Chanel and the enormous opportunity it presents.

Certainly everyone in Paris had an opinion about who would be good for Chanel. Sliding into my seat at Armani — one of his best collections in years, based on pearls — I heard an editor claim she knew a British designer who’d already been called in for interviews. Over dinner at Voltaire with three young friends who work for big brands, one of them said, “Okay, who do we all think for Chanel?” and we threw down the names likes cards. There was Roseberry, who also happened to be the favorite of the Paris headhunter, who does not work with Chanel but who pointed out that its ateliers are used to working from sketches and not by copying vintage pieces, something many designers do. “They need someone who draws, draws, draws, who has ideas. Someone who makes trials on embroidery and fabrics. Daniel has a very classical way of working. I think he would be perfect.”

There was Jacobs, who received a lot of votes. He loves Chanel, he’s a classicist at heart, and he spent years working in Paris. At the Dries party, a guest told me, “I hope they go to someone young. I love the guy at Diesel — Glenn Martens. He’s extraordinary. He’s like a Demna. A true designer, not expected.” Coming out of a show, a journalist said, “You know who would be good? Nadège.” Nadège Vanhée is the gifted womenswear designer at Hermès. She has great taste, her clothes are seldom complicated, and she obviously knows about craftsmanship.

“I think they should take someone who’s European,” my French editor friend said. “I don’t think they should take someone from Texas and do Chanel. Excusez-moi, non. Because it’s a certain Parisian,” she said, meaning the ideal Coco had in mind. “People don’t know this anymore, but it’s true.”

When I caught up with Pavlovsky after the Opera show, he agreed that a change at Chanel could be pivotal. “It’s an opportunity for Chanel to continue to lead for the next 20 years,” he said.

“Do you think it needs to lead, then?” I asked.

“We have to lead. No choice.”

It bears noting that though Chanel would like to find someone with the potential to shape and reshape its fashion for many years, as Lagerfeld did, no designer is likely to enjoy his level of freedom. As an LVMH executive said, “He was the brightest creative director in the business. His long-term success came from his freedom, and his freedom came from his business acumen. Not just the artistic aspect.” But designers today don’t necessarily grasp the whole of a brand’s business because the companies are so large and complex, running like machines. How much the next designer of Chanel will be able to do will depend on factors besides talent, taste, and courage. “Sometimes the fashion system forgets that you can have all the designers that you want but it depends on the owner of the company — what is their vision? What is their plan for the future?” the creative director of a major LVMH brand told me with some wisdom. “We cannot forget that size makes a difference. If we are speaking about a brand that’s $1 billion, it’s one thing; $2 billion is another; $20 billion is another game.”